New Jersey’s robust role in the regional service, commercial, and cultural economy is closely linked to the ability to get into New York City as easily as possible. The flow of people into the high-paying Manhattan economy plays an ever-increasing part in New Jersey’s well-being. That requires preserving and expanding several key public transit facilities. A major priority will be guiding two trans-Hudson transportation projects to completion: the Gateway tunnel and terminal construction and the Port Authority Bus Terminal replacement/expansion. Without these projects, New Jersey’s role in the regional trans-Hudson economy will be stifled. (Other important projects are detailed in the appendix to this report.)

GATEWAY

No transportation capital project is more important to New Jersey’s economic future than the Gateway Program to expand and improve the rail line from Newark to Midtown Manhattan. Gateway would rebuild and supplement century-old bridges and tunnels, some of them weakened by Superstorm Sandy in 2012, to facilitate additional and faster train service on tracks shared by NJ Transit and Amtrak.7

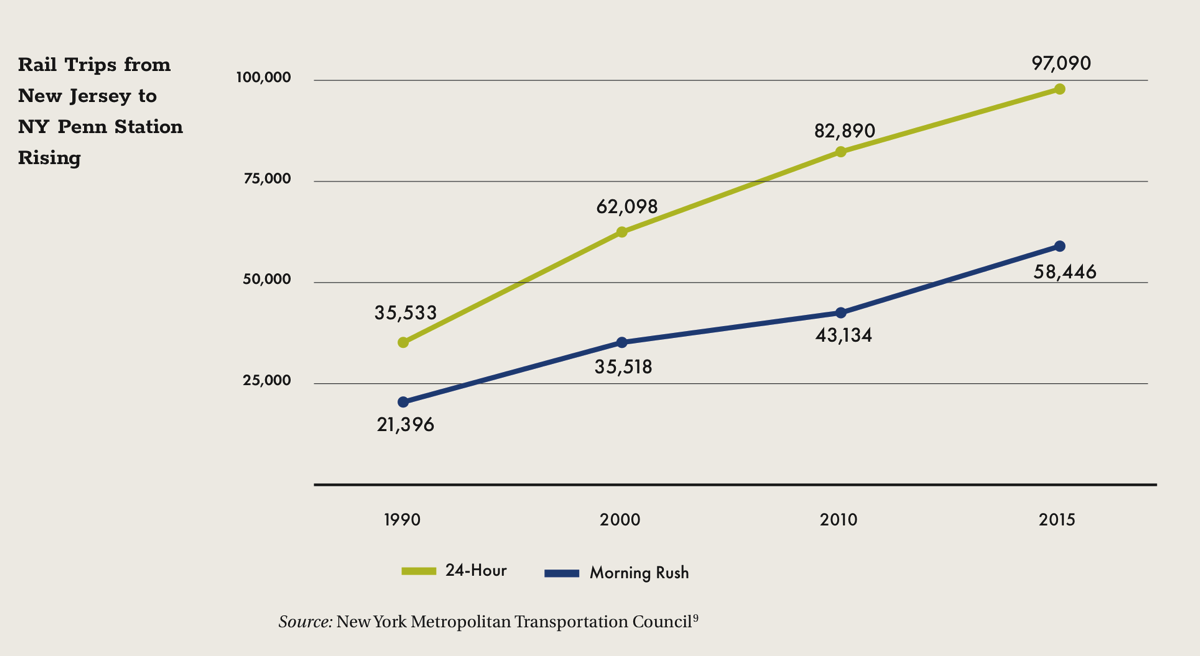

The need is clear. From 1979 through 2017, NJ Transit ridership into New York Penn Station quintupled to more than 97,000 on weekdays.8 With Gateway, the system could comfortably accommodate an additional two-thirds ridership increase.

New Jersey and New York have committed to jointly finance 50% of Gateway’s cost, provided that the federal government contributes grant funds for at least the other 50%.

With assists from U.S. Sens. Cory Booker of New Jersey and Charles Schumer of New York, the federal government during the Obama administration agreed to the stipulation, and Congress passed enabling legislation. However, the Trump administration’s budget proposal for the federal fiscal year starting October 1, 2017 did not address the early steps needed to advance the project’s financing. It is now up to Congress to lay the project’s financial foundation.10

The urgency of Gateway’s first phase focuses on NJ Transit’s swift completion of a draft environmental-impact study on the railroad tunnel. A draft published in July 2017 included revised cost estimates for rehabilitating the two 106-year-old tubes ($1.7 billion) and constructing two new ones ($11.2 billion).11 Corrosive salts left by Superstorm Sandy’s flooding are eating away at the concrete walls and electric-traction and signal systems in the tunnel. Engineers project that, in the next 10 to 20 years, each of the two tubes will have to be taken out of service for overhaul. If either tube goes out of service before a replacement is operational (estimated to be in 2026), today’s peak commuter and intercity service of 24 trains an hour (21 NJ Transit and three Amtrak) would shrink to six.12

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey took a step toward financing the new Hudson River tubes in February 2017 by allocating $2.75 billion in its 10-year capital plan for the tube project.

Replacing the Portal Bridge, built over the Hackensack River in 1910, with a higher span means trains on the nation’s most important passenger rail corridor no longer will have to stop for water craft passing underneath. Engineering and environmental work for the project is finished, so construction could begin as soon as funding is assembled. A House Appropriations bill for the next federal fiscal year provides $500 million from the Northeast Corridor State of Good Repair program toward construction of the new fixed, high-span North Portal Bridge. Senate action is pending. Some $21 million in state money also has been allocated toward this project.

RECOMMENDATION

Make nurturing Gateway’s array of projects toward their realization the top New Jersey transportation priority.

The projects’ high cost (estimated at $24 billion to $29 billion), multiyear construction, and complex institutional relationships and financing will require consistent monitoring.13

Pay immediate attention to advancing and financing the lead elements of the first phase: constructing two new rail tubes into New York Penn Station, rebuilding the existing two North River tunnel tubes, and replacing the Portal Swing Bridge over the Hackensack River between Kearny and Secaucus.

Beyond monitoring Phase One, shape, finance, and advance Gateway’s Phase Two as a crucial investment in New Jersey’s economy.

Phase Two includes expansion of New York Penn Station’s platforms and tracks to a “Penn South” annex, and construction of the Bergen Loop, a track connection from the Bergen County, Main, and Pascack Valley lines to the Northeast Corridor. Phase Two would be finished in 2030, in tandem with completion of the refurbishing of the existing tubes.

Construction of new tubes alone does not do anything except avert disaster. These Phase Two projects, along with the new Gateway tunnel in Phase One, would enable NJ Transit to run at least 34 trains in peak hours, up from today’s 21. Benefits would include eliminating transfers in Newark and Secaucus Junction for riders on the Raritan Valley, Bergen County, Main, and Pascack Valley lines. And additional capacity would enable other lines to expand service to increase the number of trains on the Northeast Corridor, North Jersey Coast, and Morris and Essex lines.

However, securing future financing for Phase Two will be challenging because of the uncertainty of Trump administration policy, sectional tugs and pulls in Congress, limited Port Authority and NJ Transit resources, and New York state’s grudging participation.

Another facet of the second phase of the Gateway Program should be consideration of a proposal being developed by the Regional Plan Association to design Penn South not as a terminus but as a facility that trains could pass through on their way to other destinations.14 Penn Station would be retrofitted to have fewer tracks, wider platforms, and new tunnel connections to Sunnyside Yards in Queens. The RPA is advancing this design because it is thought to add eight to 10 trains per hour in trans-Hudson rail capacity.

This expanded capacity would more easily accommodate demand for direct service from northeastern New Jersey (Bergen Loop) and from other lines, service that might not be met by the current Penn South plan.

REPLACEMENT/EXPANSION OF THE PORT AUTHORITY BUS TERMINAL

The second essential trans-Hudson transit project is replacement/expansion of the Port Authority Bus Terminal, which anchors the Lincoln Tunnel corridor. The bus terminal accommodates nearly 50% of the existing daily trans-Hudson transit trips, handling 260,000 riders per day with 7,900 daily bus trips in or out of the terminal. And the bus terminal’s role will increase: Port Authority staff have forecast the number of passengers using the Lincoln Tunnel corridor will grow 35% to 50% by 2040.15

Planning the future of the bus terminal has been contentious.

The Port Authority’s Board of Commissioners first determined in 2016 that the terminal, located between Eighth and Ninth Avenues and 40th and 42nd Streets in Manhattan, was near the end of its useful life. The terminal, then 66 years old, could not accommodate the growing demand of commuters; newer buses were having a difficult time negotiating the terminal’s ramp system, bus passageways, and platforms; and the concrete slabs supporting buses were predicted to crack and become unusable within 20 years.16 A study analyzing the feasibility of building a smaller terminal in concert with alternative projects found that no more than 10% to 20% of bus demand could be siphoned off from the replacement facility. The study concluded that a new bus terminal should be designed with ease of expansion in mind.17

Assuming that rehabilitation of the existing structure would be too disruptive, the board identified a 3½-block site on Ninth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan for a new terminal. (The existing terminal would be re-purposed into an office building, with the proceeds offsetting some of the project’s estimated $10 billion cost.) The choice proved unpopular. Elected officials and neighbors of the selected site opposed the construction of a huge facility there. The proposed relocation also raised concerns about whether riders could easily connect to the subway stations on Eighth, Seventh, and Sixth Avenues, and about lengthened walks to Midtown office destinations.

In response, the board authorized $70 million in February 2017 to begin a comprehensive environmental planning effort on replacement of the bus terminal as well as support facilities for bus storage and staging. This planning would also examine intermediate bus storage and staging facilities, including Port Authority-owned properties in West Midtown Manhattan and in New Jersey. A decision document is anticipated in 2019.

In parallel, the Port Authority board announced that the viability of a new “build-in-place” facility—the concept it had once ruled out—would be evaluated. The board expects to learn in fall 2017 from an independent consulting engineer whether the option to rebuild on the existing terminal’s footprint is feasible, how long it might take, and how much it might cost.

The issue of how to pay for the terminal is also contentious. The Port Authority’s 10-year capital program includes $3.5 billion for the replacement/expansion project, including funds for a bus storage/staging facility that directly connects to the exclusive bus lane.

Recognizing that this amount is unlikely to provide for the replacement/expansion of the bus terminal, the Port Authority board authorized retaining a financial consultant to assess available federal funding as well as private capital and investment interest.

Additionally, $328 million has been authorized in the 10-year capital plan for intermediate measures to improve operations and conditions at the bus terminal. These include making structural and leak repairs, updating building infrastructure, and completing the Quality of Commute program, which includes restroom, elevator, and escalator rehabilitation as well as the addition of cellular and wireless connectivity.

RECOMMENDATION

Pay close attention to every detail of the new Port Authority Bus Terminal project, making sure New Jersey’s interests are protected.

The importance of a new bus terminal to New Jersey commuters requires focused commitment to guide the project’s development—and, possibly, survival—in the following ways:

- Protect and expand the Port Authority’s capital plan commitment to the project

- If necessary, aggressively seek federal support for a portion of the project’s cost

- Make sure the project includes an assurance that road links connecting to the Lincoln Tunnel can accommodate the growing number of buses and that convenient connections to the subway system and pedestrian street network are provided

ASSESSING THE PORT AUTHORITY’S FINANCIAL ROLE

Since its founding in 1921, the Port Authority has grown into a major source of funding for important transportation operations in the two states—assistance that, in other major metropolitan areas around the world, often comes from general taxes. To finance construction and major maintenance projects, the Authority borrows money through the sale of bonds and repays the bondholders with revenue from tolls and fees.

It is important for policymakers to realize that the money-raising capacity of this model is eroding. The Port Authority is completing a major sequence of bond-financed projects at the World Trade Center site, and its debt service is affecting its financing abilities. Moreover, today profit-making tunnels, bridges, and airports in large measure subsidize such unprofitable operations as PATH, the Port Authority Bus Terminal, and the World Trade Center. With a four-year sequence of river-crossing toll increases having only recently been completed, the Port Authority no longer can easily “grow the pie” of operating revenues to support new investment.

Gaining a clear view of the financial capacity of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey will be essential. Taking into account pressures from New York state to commit to projects New York desires (in particular, airport improvements), New Jersey will have to determine (1) how much financing the Port Authority can offer the Gateway Project, (2) how much funding is needed and can be secured to replace the Port Authority Bus Terminal, (3) what other projects are of special benefit to New Jersey, and (4) how best to take advantage of the Port Authority’s potential sale of its real estate holdings that are no longer essential to its mission.

RECOMMENDATION

Reach consensus with New York state on the Port Authority’s financial capacity to take on loss-making projects and evaluate what steps are necessary to maintain its ability to self-finance capital improvements.

Relying on operating revenue to issue bonds that finance loss-making infrastructure projects will be difficult in the foreseeable future. Care must be taken to temper expectations that vast Authority resources of the past will be available to support new projects to the same extent.