New Jersey gives short shrift to the two transportation entities with the largest roles in delivering a well-run, efficient system:

-

The state Department of Transportation (NJDOT), established in 1966 to replace the State Highway Department. Its major responsibilities, broadly defined, include creating and maintaining a master plan for transportation development and building and maintaining the state’s system of highways and bridges.

-

NJ Transit, a state-owned system of bus, commuter rail, and light rail services that carries the third highest ridership in the U.S. It was created in 1979 to “acquire, operate, and contract for transportation service in the public interest.”18

It is essential to reverse the destabilizing impact that state budgeting practices have had on the work of the state Department of Transportation and NJ Transit.

ENGAGING THE PUBLIC

For years, state leaders have downplayed the severity of New Jersey’s transportation funding crisis. They missed the opportunity to build public understanding and support for infrastructure investment and good transportation policy.

As the state’s economy and the world of communications technology continue to evolve, years have gone by without NJDOT and NJ Transit launching a public discussion that would lead to a new vision for transportation investment and the state’s roles. As a result, the public’s constant complaints about traffic congestion, lost time, and gaps in mobility remain unanswered. The state agencies need to engage New Jersey residents and workers on these issues.

The state of Washington offers a good model. Its quarterly publication, the Gray Notebook,19 reports on transportation performance, including updates on the status of planned projects.

RECOMMENDATION

Create an online information tool to better inform New Jerseyans about transportation issues and priorities, and to help restore public confidence in how the state deploys capital resources.

Public involvement through discussion at traditional “town hall” sessions and in social media could launch more inclusive and interactive transportation policymaking. Results might include grassroots support for pedestrian and bicycle safety and for managing congestion through communications technology, such as more traffic lights on state and county roads that are timed based on traffic flow and more message signs for motorists.

EFFECTIVE LONG-RANGE PLANNING

Over the past decade, NJDOT and NJ Transit have been unable to prepare a long-range transportation plan that bears the governor’s endorsement. Three other organizations that do this kind of work as part of their federal mandates at an acceptable level of quality are the state’s Metropolitan Planning Organizations: North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, and South Jersey Transportation Planning Organization. In fact, NJDOT has assigned to these organizations the responsibility of updating the Strategic Highway Safety Plan.

RECOMMENDATION

Under the leadership of NJDOT, direct the staffs of NJ Transit, the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, and South Jersey Transportation Planning Organization to jointly conduct long-range planning.

For this model to work, the Governor’s Office would have to be fully involved. A “vision” plan prepared in this integrated fashion would likely increase public participation and attract greater support than have previous plans.

NJ TRANSIT

The state budget is the main source for bridging the annual difference between transit operating expenses and revenues from such sources as fares and the sale of advertising space on trains and buses. This annual deficit is now at $1.1 billion.

In the early 2000s, the General Fund of the New Jersey state budget contributed approximately $350 million toward NJ Transit’s operating deficit. By the fiscal year that started July 1, 2015, that support was down by 90%, to $33 million.20

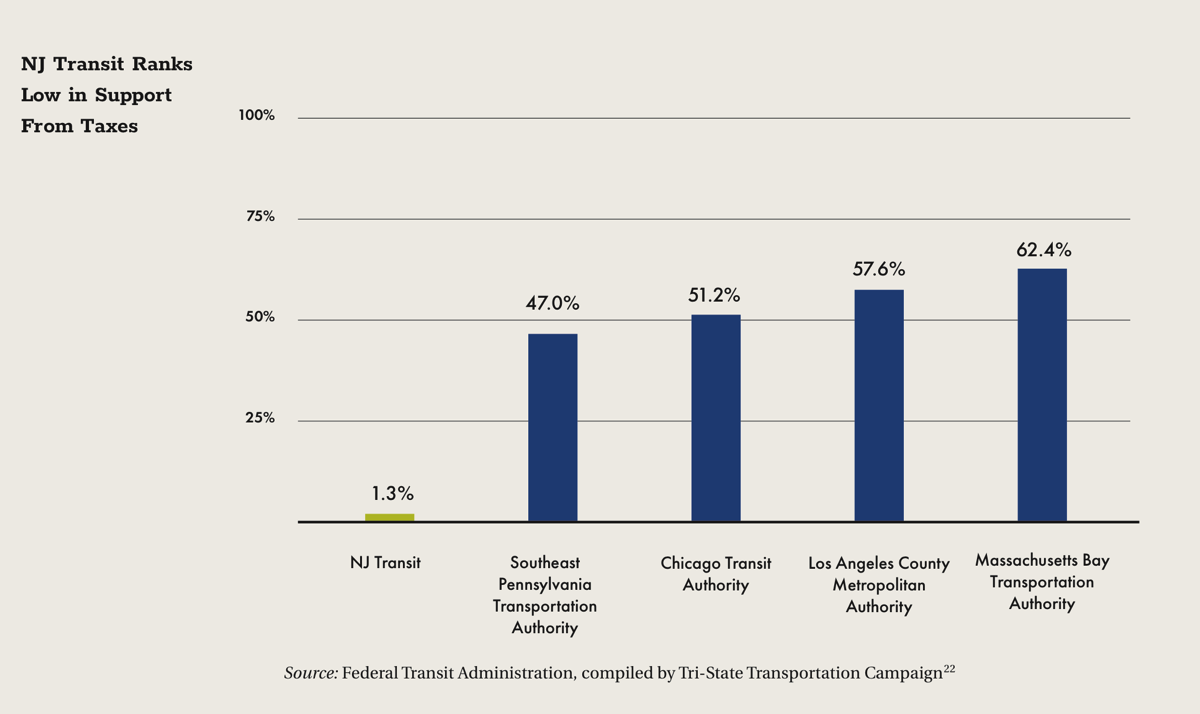

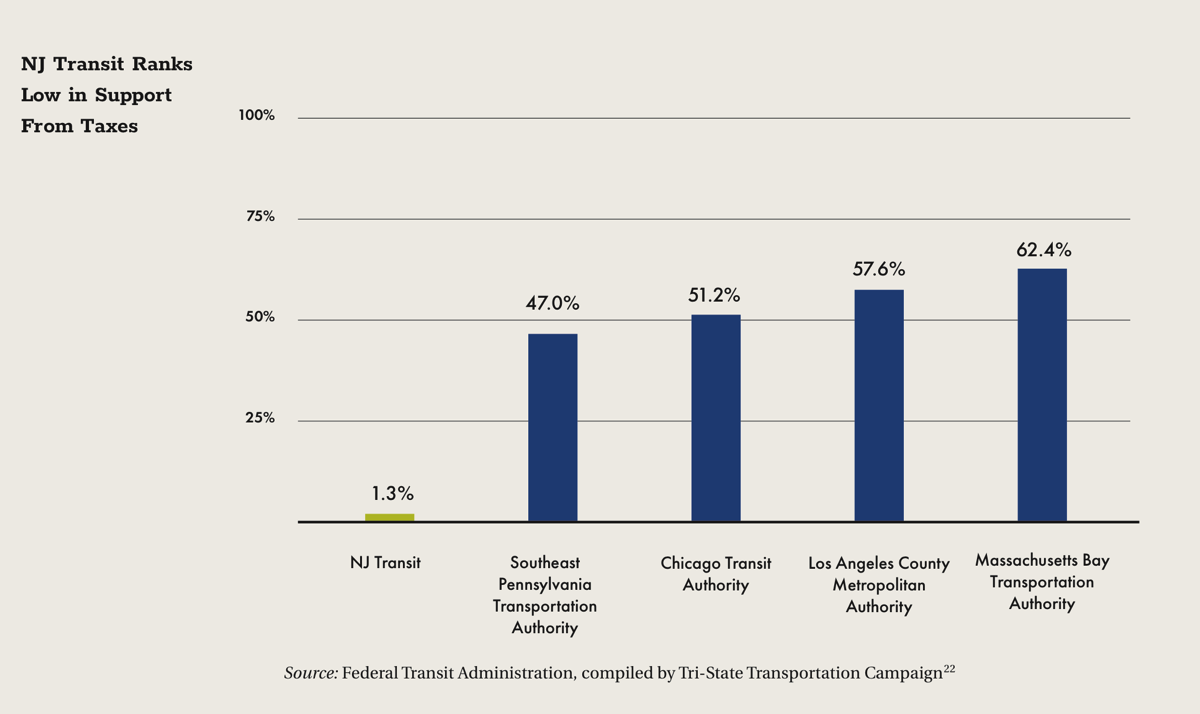

Public transit agencies in many other states can depend on annual revenues from the state budget. For example, dedicated taxes contribute between 47% and 62% of operating assistance for systems based in Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Boston.21 NJ Transit has no such cushion.

A major byproduct of state budgetary neglect has been heavy reliance on fare increases. A 2015 New Jersey Association of Rail Passengers study reported that NJ Transit riders paid higher fares for a 50-mile trip than passengers of comparable U.S. commuter rail agencies.23 As of 2012, fares made up 52% of NJ Transit’s revenues, compared with 34% to 38% in such comparable metropolitan areas as Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston. NJ Transit has raised fares five times since 2000, including a record 22% hike in 2010.24

Because of reluctance to raise taxes that would strengthen revenue flows to the state’s General Fund (in fact, some state taxes were reduced to win legislative and gubernatorial support for raising the gas tax), competition for allocations has intensified. NJ Transit is a victim of that competition. The agency has persistently lacked resources, resulting in the loss of several key staff members to other regional transportation agencies after almost a decade of no pay increases and creating vacancies in important authorized safety-compliance positions.

One factor contributing to constant scarcity and instability is the longstanding practice of devoting a sizable amount of federal transit capital dollars, in the absence of state operating funds, to preventive maintenance. More than $400 million annually is diverted in this way, a practice begun in the late 1990s. Restoring this money to its intended use would strengthen a NJ Transit capital budget that remains fragile and insufficient even after the 2016 Transportation Trust Fund re-authorization.

RECOMMENDATION

End reliance on federal capital-to-operating transfers, as has the Chicago Transit Authority and Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA).25

Beyond relying on capital money to pay for operating expenses, NJ Transit’s budget suffers from instability caused by temporary fixes that paper over shortfalls.

Drivers might be surprised to find out that the tolls they pay on the New Jersey Turnpike have become a major component of the transit agency’s annual operating budget. For three years, some $295 million per year from the last Turnpike Authority toll increase, originally allocated to the Hudson River tunnel, was used to cover part of NJ Transit’s operating budget deficit. This diversion occurred under a provision in the arrangement consolidating New Jersey’s toll authorities that loosened restrictions on the use of Turnpike Authority revenues. In the state fiscal year that began July 1, 2017, the Turnpike Authority’s contribution was $204 million.26 Allocating Turnpike revenues to NJ Transit regular operations both masks the budget gaps and diverts funds that could be used appropriately for NJ Transit capital improvements.

The state Clean Energy Fund is another temporary fix for these budget gaps. Intended to promote ways to reduce energy consumption, and derived from assessments on utility customers, the fund increasingly is being used for NJ Transit operations: $82.1 million in the most recent two budgets and $62 million two years before.27 Energy-conservation advocates understandably contend that supporting NJ Transit’s annual operations is not an appropriate use of utility-bill assessments.

RECOMMENDATION

Eliminate temporary, inappropriate funding sources for the NJ Transit operating budget and the uncertainty that threatens stability and efficiency. Evaluate options for new, stable revenue sources.

Strong consideration should be given to ending dependence on Turnpike Authority revenues to provide stability for NJ Transit’s future operating budgets. Turnpike funds could appropriately be used to support NJ Transit capital improvements, but operating support must come from other sources.

Better options for the NJ Transit operating budget include (1) using motor vehicle license and registration fees, beyond sums needed for Motor Vehicle Commission improvements, to support NJ Transit, and (2) devoting to NJ Transit new taxes on real estate transactions or business payrolls, following the pattern of the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority.

NJ Transit is governed by a board of directors chaired by the state commissioner of transportation. The other six members are the state treasurer, a member selected by the governor from his or her administration, and four “public” members nominated by the governor and confirmed by the state Senate. The four public members, often business people or lawyers, do not represent any specified constituencies.

The board structure has not changed since it was established in 1979. Now is a good time to revisit that structure, with an eye toward governance that better represents the wide range of New Jerseyans who have interests in a smooth-running public transportation system. For example, people who ride the system could bring sensitivity to users’ needs, business people could help guide the operation of a public enterprise, and elected officials who have served on transportation boards, such as the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority, could offer knowledge of the economy’s needs. Such criteria could inform the selection of future board members.

RECOMMENDATION

Change NJ Transit’s governing structure to be accountable to the public and representative of everyone with a stake in a strong mass transit system.

A good start would be creation of a panel to advise the governor on proposed legislative criteria for selection of NJ Transit public board members. The commissioner of transportation should continue to chair a revamped NJ Transit board, and the state treasurer should continue as a member.

N.J. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

In most states, transportation needs (or at least highway needs) are funded from dedicated trust funds, relying mainly on gasoline taxes. These funds support both the capital and operating costs of the agency. New Jersey chose a different model. In the 1970s, after decades of inadequate, unpredictable financial support for transportation, policymakers rejected the idea of a trust fund that would support both capital spending and operations, instead enacting a single purpose fund devoted solely to capital expenditures. Support for daily operations and maintenance needs, as opposed to major construction projects, was left to annual appropriations from the state budget, and this practice continues today.

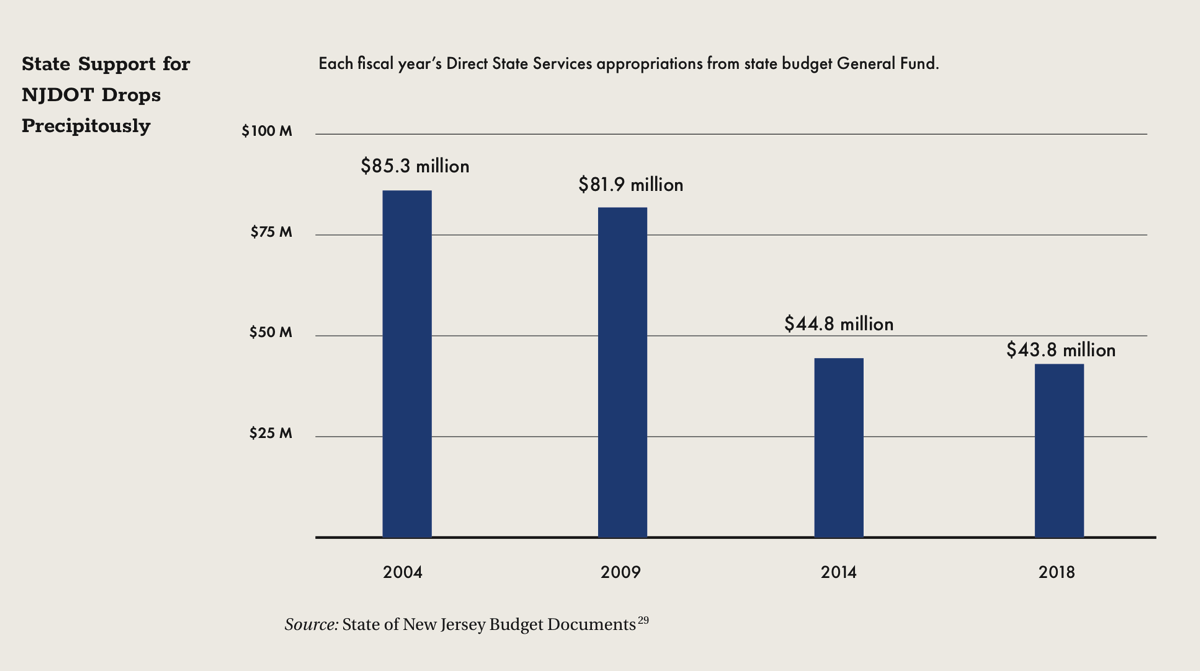

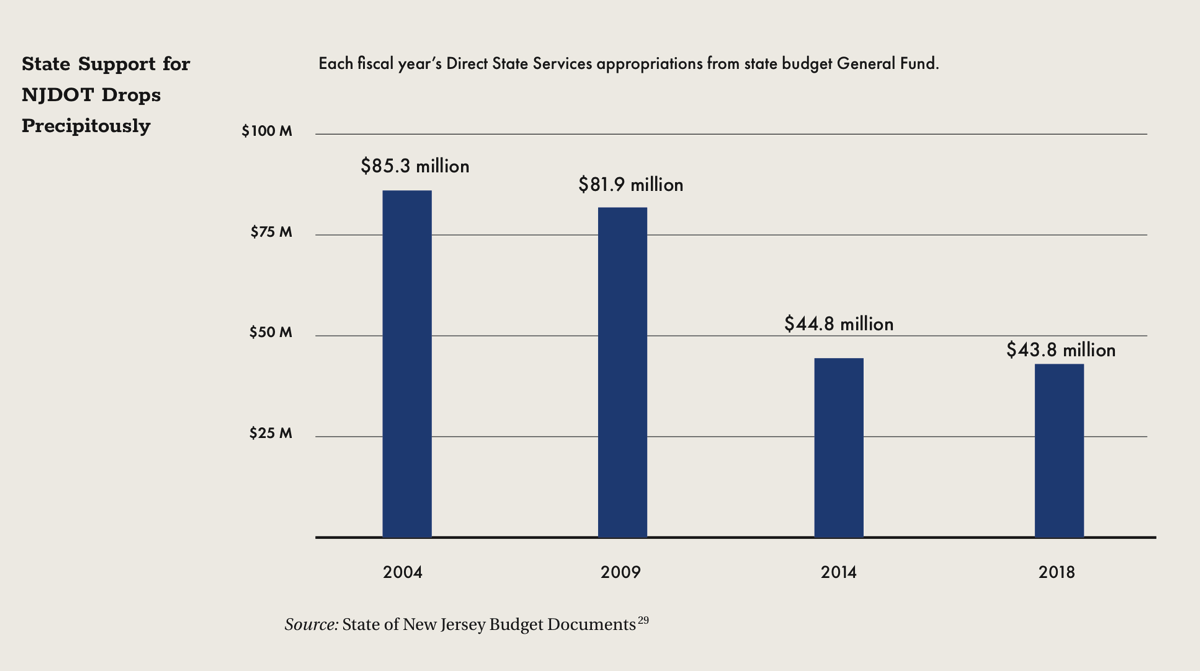

Over the past three decades, reliance on funding operations and maintenance from the state’s General Fund has turned out to be a bad deal for New Jerseyans who depend on a reliable transportation system. NJDOT’s allotment from the state budget has been tightly squeezed—from $85 million in the fiscal year that began July 1, 2003, to only $43 million in the current fiscal year. This squeeze is even more remarkable when inflation on the purchasing power of the 2003 appropriation is taken into account.28

Gubernatorial administrations, legislators, and policymakers at NJDOT often appear more concerned with the “optics” of expenditures than with efficiency (for example, by publicizing staff reductions as cost savings), leading to chronic staff shortages in key areas, restricting workers’ professional development opportunities, eliminating office administration tools, and other negative consequences.

The continuing squeeze on the NJDOT operating budget can be seen in numerous vacant positions and the resultant designation of “acting managers.” As state appropriations have declined, management salary increases have been rare, leading to a hollowing out of the management structure. Few employees seek management positions, because classified civil service positions hold the promise of salary increases over time and management positions do not. Inadequate numbers of support staff such as accountants lead to project delays and cost increases. Reductions in engineering staff increase reliance on private engineering consultants, which makes road construction more expensive.

A decline in operations and maintenance quality that would correspond to the sharp decline in appropriations is avoided only by shortsighted budget maneuvers, most commonly “capital-to-operating transfers” that divert money from major projects to fund day-to-day expenses. The capital budget, intended for construction projects and major improvements to the transportation system, now includes such items as salaries, preventive maintenance, and purchasing equipment such as roadway lighting. In the past, these routine expenditures came from state General Fund appropriations.

Shifting operating costs to financing through bonded indebtedness is a particularly costly practice. Due to interest incurred over the life of the Transportation Trust Fund’s long-duration bonds, New Jersey ends up paying nearly double the original cost. More disturbing is the fact that the same activities such as resurfacing or guard rail replacement will be repeated on the same piece of roadway three or four more times before the original bond is retired.

These state budgeting practices contribute to a decline in the overall transportation network by diverting millions of dollars in capital funds for operating purposes and deferring both routine maintenance and intermediate roadway and bridge rehabilitation projects.

While seeking better ways for public investment to meet the state’s transportation needs, policymakers have the opportunity to consolidate state transportation entities and take advantage of these entities’ organizational, policy, and financial strengths to address system weaknesses.

RECOMMENDATION

Bring the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and South Jersey Transportation Authority into NJDOT. The commissioner of transportation would chair this new super-authority.

Except for the 2003 merger of the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and the New Jersey Highway Authority (which oversaw the Garden State Parkway), the structure of New Jersey’s transportation agencies has been largely unchanged for more than three decades.

The skill shortages and resource scarcity that have weakened NJDOT might be best addressed by such a merger. The merged professional and administrative workforce would be subject to the Turnpike Authority’s salary and employment regulations, which are more comparable to the private sector. Recruitment efforts could be strengthened through better salaries and broader career opportunities. Efficiency could be enhanced by the flexibility to assign workers where they are most needed, while reducing expenses for administrative functions and duplicative space. New funding streams could be developed through future toll increases.