As indicated above, there is strong agreement that New Jersey’s fiscal problems are connected to insufficient state payments into retirement funds for public workers, including state, local, and judiciary workers, teachers, police, and firefighters. Based on such factors as the number of retirees,8 their projected life spans, and the benefits approved by the state,9 New Jersey’s unfunded employee pension obligations as of July 2016 were at least $66.2 billion.10 A much higher estimate is generated using the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) protocol. GASB estimates are based on more-conservative assumptions about market values of current assets, a continuation of low state contributions, and minimal investment returns. The resulting GASB calculation of the pension plan’s unfunded liability is $135.7 billion. The actual size of the unfunded liability could be in between the two estimates.

Regardless of which approach is used to estimate the total unfunded pension obligation, the problem caused by underfunding the system grows every year. The state portion of the unfunded actuarial accrued liability increased nearly $20 billion from 2009 to 2016 (to $49 billion from $29.6 billion).11 For reference, the state’s contribution to the Teachers’ Pension and Annuity Fund just in the fiscal year starting July 1, 2017, is statutorily required to be $2.99 billion — and $2.63 billion of the total is due to the accrued liability. Yet the state is expected to appropriate $1.49 billion at most. The system will remain broken until enough payments are directed to the unfunded portions of all of the plans. If the assets of any pension fund are depleted and the courts require that the pensions must be paid, the state would have to take the funds, more than $8 billion annually12 to cover the judges, teachers, and other public workers, out of the budget and away from other priorities.

Only nine states have a larger unfunded pension gap than New Jersey’s.13 The problem reflects the confluence of several factors, including:

- Decisions since 1994 to underfund annual required state payments into the pension plans

- Borrowing to finance underfunded pension plans, incurring debt costs that placed an additional burden on the budget

- Declines, induced by the 2008 recession, in earnings on the investments made using retirement funds

- An increase in 2001 in the level of pension benefits, which resulted in higher costs without identifying an ongoing means to fund them

- Increased volatility in investments' rates of return (a reflection of erratic markets), leading to changes in asset allocation to more, and riskier, equity holdings – especially since the late 1990s – and to alternative investments that incur higher fees

- Retirees' increasingly longer lives, resulting in pension contributions from current workers supporting fewer retirees than before

The bulk of the current problem can be traced to governors and Legislatures trying to balance budgets without imposing adequate tax increases or spending cuts. Instead, they simply skipped payments into the pension fund or made annual payments that were less than the annual required contribution (ARC) needed to avoid falling behind on retirement benefit funding.14

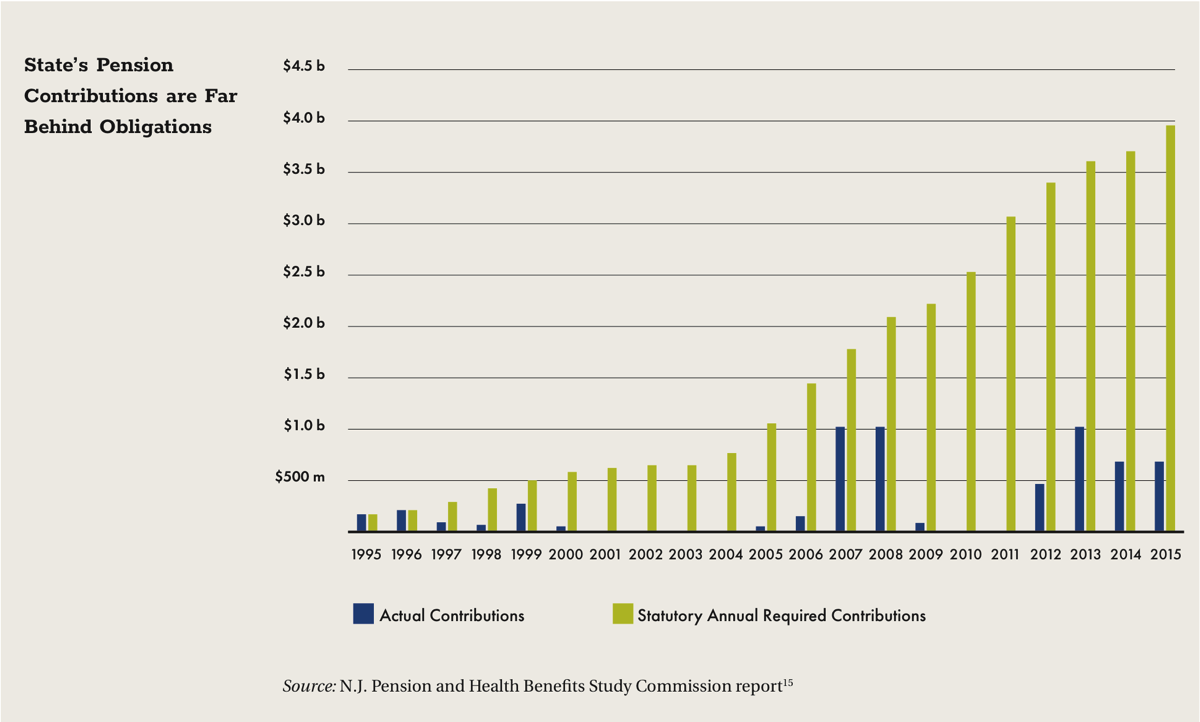

The chart above, produced by a commission convened by Governor Christie in 2014, shows how the ARC increased exponentially when the previous year’s payments were insufficient. Although public workers continued to contribute as required, the state’s failure to contribute its share, coupled with the loss of potential investment earnings on those missed payments, is at the heart of the underfunded pension problem. The power of compound interest has worked against New Jersey for years, leaving the state under a mountain of debt. As with prepaying a mortgage, compound interest can help us: putting in more money now reduces the future principal. New Jersey will regain its fiscal footing only if the state begins, now, to make the full payments required. If we keep delaying, the obligation will continue to increase.

A law enacted in 2011 required employees to immediately begin to increase their contributions to the pension funds. In the case of PERS and TPAF, contributions increased to 7.5% of salary by the fiscal year starting July 1, 2017. When the law was enacted, the state vowed to make its annual payments, moving incrementally toward full ARC funding in that same fiscal year. As the New Jersey Pension and Health Benefits Study Commission chart shows, the state did not live up to the agreement. Rather, in 2015, the administration put the state on track to reach full funding of the ARC in the fiscal year that begins July 1, 2021, a delay that added to the accumulated unfunded liability.

As serious as the state’s unfunded pension liability is, it is equaled by the challenges posed by other retirement benefits, primarily, health coverage for retired workers and their dependents. A legal obligation to provide these benefits is less likely (courts in other states have upheld cuts in retiree health coverage), but the unfunded obligations are large and, given longer life expectancies and steadily increasing health care costs, may grow at an even faster rate than the funding gaps in the state’s pension system. Moreover, the state no longer maintains reserves to help offset the cost of future benefits, which are funded on a pay-as-you-go basis.

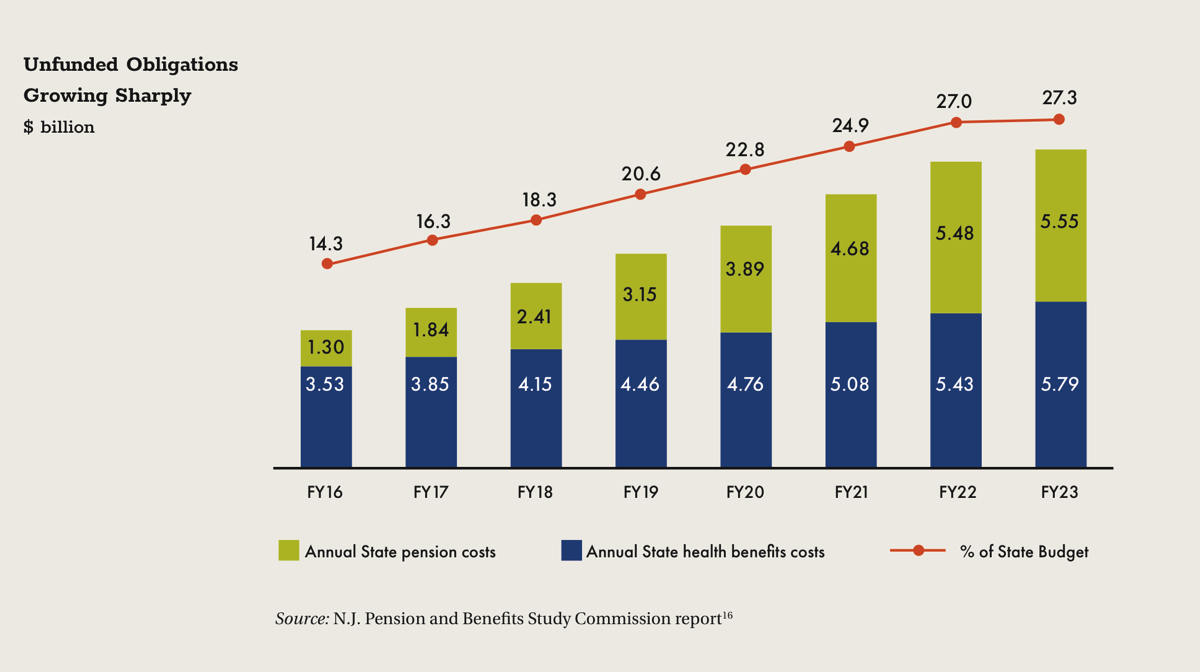

The commission chart below shows the state health benefits costs (light blue) and the state pension costs (darker blue) in billions of dollars, and as percentages of the state budget, projected through the fiscal year that begins July 1, 2022. The order of magnitude of these underfunded employee retirement obligations is alarming.

Recent analysis by the J.P. Morgan financial services firm helps to put the situation in context.17 Using the acronym IPOD, the analysis focuses on efforts required by individual states to meet the following fixed obligations: interest on bonds (I); payments to meet obligations for defined-benefit pension plans (P); other post-employee retirement benefits (O); and payments for state-defined contribution retirement plans (D).

The calculation for New Jersey shows that the state’s obligations in these IPOD areas equal 12% of current total state revenues, and that the cost of meeting all future obligations accrued to date would be 38% of the current budget. The analysis examined three options available to the state to meet those obligations: increasing taxes, cutting state spending, and increasing the contributions made by state workers to their retirement benefits.

If the state chose to meet its obligations only through raising taxes, those taxes would need to increase by 26%. If the approach was only to reduce state spending in areas other than employee retirement, those cuts would amount to 24% of current spending. If, rather than tax increases or spending reductions, the obligations were met solely by raising the amount that workers contribute to their retirement benefits, those contributions would have to nearly quintuple. Underscoring the impracticality of each strategy is the need to keep each in place for 30 years, with all the money raised dedicated solely to resolving the retiree benefit underfunding. None of these options is politically feasible or in the best interests of promoting the state’s overall growth and well-being.

Important choices loom for New Jersey policymakers and residents. Given the significance of the state’s fiscal problems, some widespread pain will be in the offing as the state scales back valued services and seeks to raise additional revenues. There is no viable alternative. Opportunities to achieve economies through spending reductions are relatively modest, however, and additional future resources will have to be generated via higher taxes. Postponing action will only make the problem worse.

RECOMMENDATION

Adopt a balanced and multi-pronged approach that combines spending reductions and revenue increases to address the gap created by years of underfunding retirement benefits and to generate the additional resources necessary for public investments that build a thriving economy for everyone.

A balanced approach could include:

- Curtailing health care costs for retired public workers, which have increased dramatically. Reducing coverage to levels commensurate with leading private employers (“gold level” plans) would produce an estimated $1.4 billion in annual spending reductions for the state, savings that could be redirected to paying the unfunded pension liability.

- Reversing state tax reductions approved when the state gas tax was increased to replenish the Transportation Trust Fund. This action alone would restore approximately $1.3 billion a year lost from phasing out annual estate/inheritance tax revenues, reducing the income tax on retirement income, reducing the state sales tax rate, and other tax cuts introduced as part of the TTF refinancing agreement.18

- Adjusting the state’s Gross Income Tax to increase yearly revenue by 10%. This action alone would produce approximately $1.4 billion in additional annual revenue.

- Increasing the rate of the state’s general sales tax to 8%, equal to the combined state and local rate in Philadelphia, less than the combined rate in New York City, and equal to or less than the combined rate in most of the rest of New York State. It stood at 7% before the Transportation Trust Fund measures were approved in 2016. The increase also would provide an additional $1.4 billion in annual state revenue.

The combined result of these spending and revenue reforms would generate more than $5 billion in additional, recurring annual revenues that could be used to meet the state’s employee retirement obligations as well as to make necessary public investments in other areas. These reforms are starting points for political discourse. They are unequivocally the scale of change necessary to avert the looming fiscal crisis.