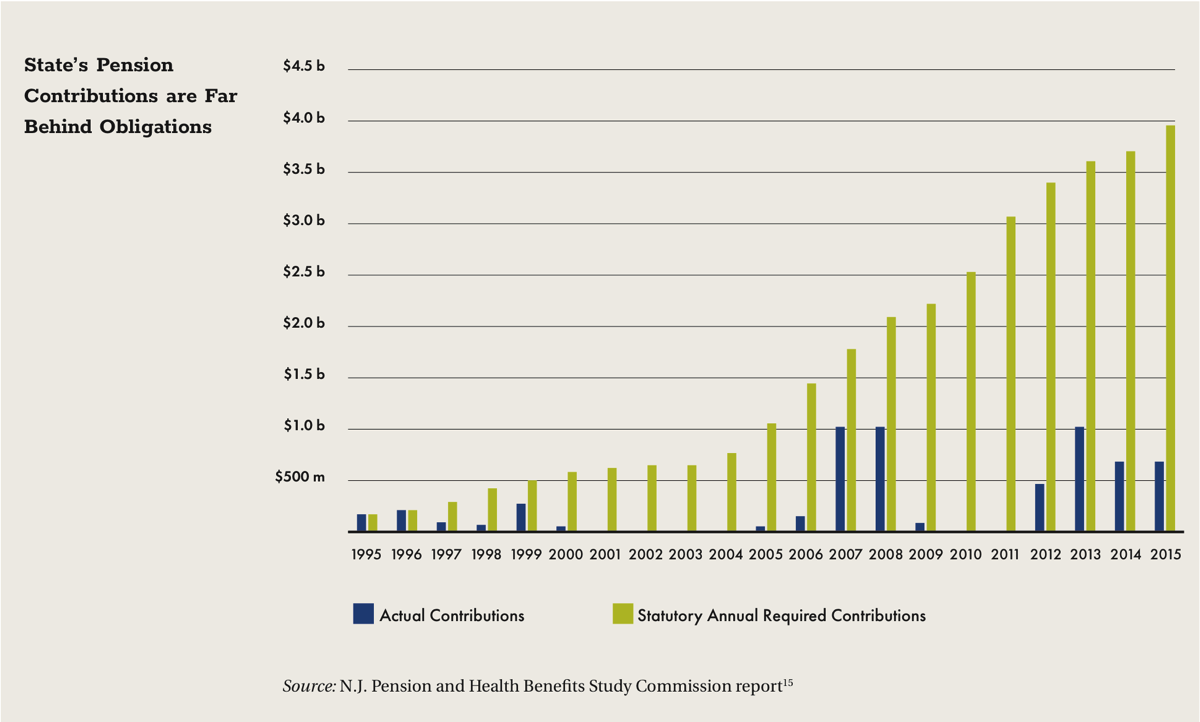

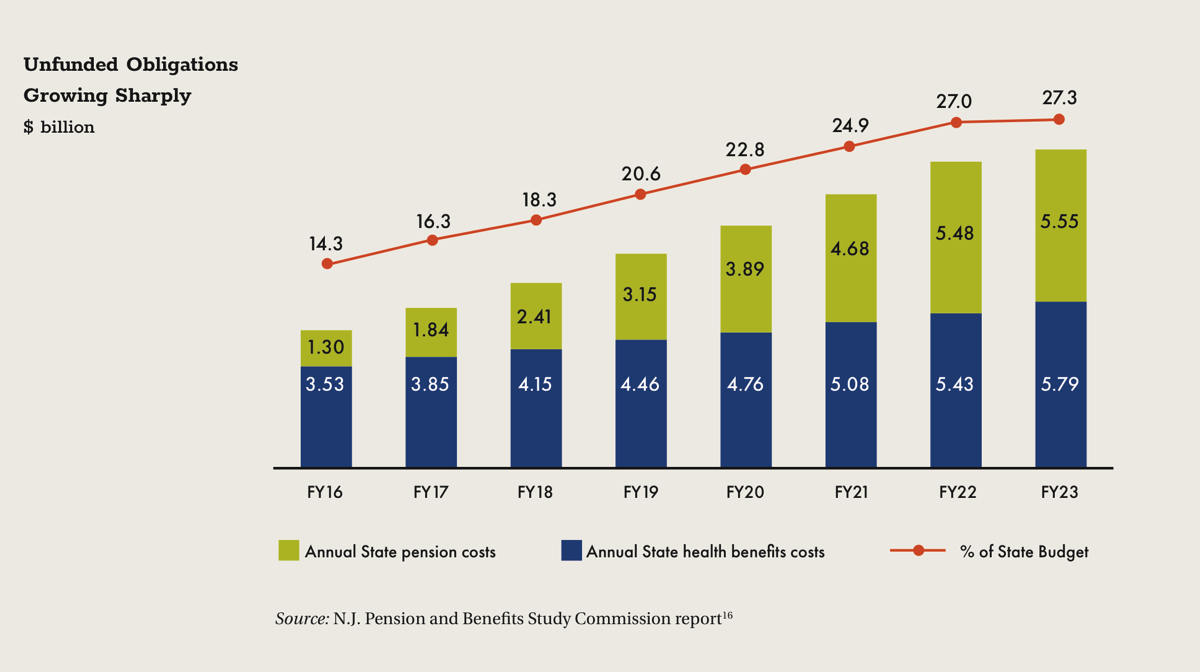

The most immediate fiscal policy problem also is the most critical: the huge gap between what the state sets aside for pensions and health care for retired government employees and how much those obligations will cost. When states pay less into the retirement systems each year than what will be needed to meet future demands, a fiscal time bomb is created. Each year of inadequate funding compounds the difficulty.

If New Jersey does not ramp up its contributions, the pension funds will run dry shortly. The projected depletion dates – when a plan’s assets cannot cover obligations to retirees – are uncomfortably near. Although estimates vary (based on differing assumptions about the state’s future contributions, the yield of the investments, and the value of payments to retirees), one projection is that in five years, that is, 2022,1 the pension plan for judges will run out of funds. According to Moody’s Investors Service, the teachers’ pension fund (TPAF) and the public employees’ retirement system (PERS) will run out of funds in 2027 or 2028.2 The state’s police pension fund (SPRS) is projected to hit zero in 2033.3

In all, more than 600,000 current and former public servants – including police officers, teachers, and social workers – could see their pension payments greatly reduced or stopped. And, because of the enormous sums needed to fill the pension gap, the crisis has implications beyond what retirees face. A cash-strapped state government cannot make necessary investments in schools and bridges, water systems, child welfare, or any of the other goods and services upon which the public depends. This is why the pension issue must be of immediate concern to everyone in New Jersey.

If the retirement plans were depleted, the state would need to devote more than $8 billion each year to pensions alone, which would displace spending in all other budget categories. Further, such pay-as-you-go spending is so fiscally unsound that it would result in continued downgrades of New Jersey’s once-stellar AAA credit rating and would increase the state's costs of any borrowing.

There are those, including some experts who advised The Fund for New Jersey in the preparation of this report, who believe New Jersey is already past the point of no return — that years of missed or inadequate investment in employee pensions cannot be undone. New Jersey’s unfunded retirement obligations over the next 30 years are so enormous – the smallest estimate exceeds $66 billion4 – that replenishing might seem impossible.

New Jersey cannot hide from this threat. Unlike insolvent companies or people, states cannot file for bankruptcy protection. As long as states have the power to raise revenue, they must do so to meet their constitutional obligations. If the pension funds were depleted, it is likely that courts would be asked to decide whether retired workers’ pensions are constitutional obligations that must be paid.

No one knows which groups and interests would feel the pain of a court ruling, but all of the likely scenarios are costly. If the courts ruled against the retirees, thousands of people could lose their economic security, and the cascading effects would be felt throughout the state. If courts ruled that the state is obliged to pay the pensions, the rush to find cash to cover these annual bills could destabilize the entire state budget.

The problem grows more serious each day, and there are no pain-free solutions. Every fiscal decision the state makes in the coming years must advance the goal of setting New Jersey in a new, better direction.

Pensions are not the only daunting financial challenge. Others include:

-

Retiree health care costs that steadily increase, putting pressure on annual budgets

-

An inefficient and inequitable tax system that deprives the state of resources needed to adequately support key public investments

-

Significant unmet infrastructure needs in transportation, energy, water supply, and other vital areas that have the potential to damage or disrupt future economic growth

-

Public education investments that fall short of New Jersey’s constitutional obligation to remedy educational disparities, as well as under-investment in early childhood and higher education, which support economic growth

-

A large and increasing number of residents, including children, who do not have enough resources to support their basic needs, including housing that is safe, healthy, and affordable

In sum, taken together, these challenges present a crisis requiring sober analysis, long-term solutions, and the determination by policymakers to act without delay.

Failure to confront these challenges will prevent public investment in the building blocks of a strong economy and thriving communities, as recommended in all the Crossroads NJ reports. Those recommendations include offering all students a quality education; rebuilding deteriorating public infrastructure for transportation, water supplies, energy, and waste disposal; helping all New Jerseyans afford a good home close to their work; and encouraging innovation and growth through support for business owners and workers.

These are among New Jersey’s many pressing, unmet needs — now and in the future — that we cannot afford to address.

By many conventional measures, New Jersey is among the nation’s most prosperous states. It has an ideal location, high average personal income and economic activity, a highly skilled work force, and many other physical, social, and economic assets. Given these strengths, the state should be on sound fiscal footing. The budget approved yearly ought to advance priorities for making public investments in New Jersey’s growth.

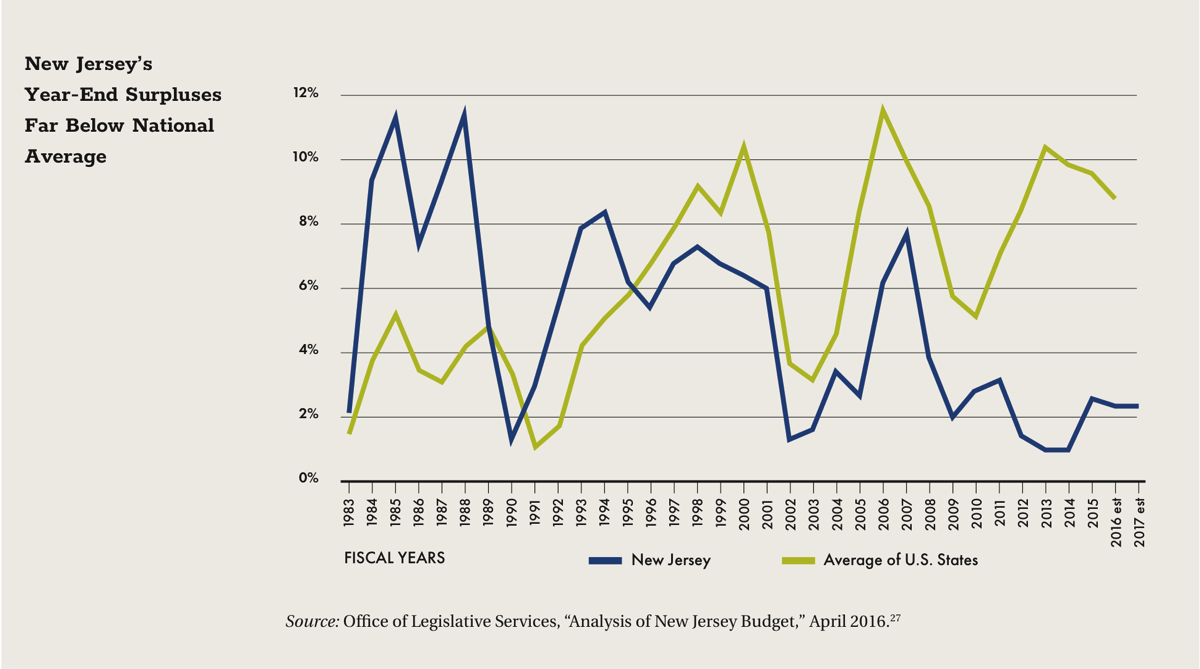

But that is not the case. Various fiscal health measures clearly demonstrate that the state’s finances are in significant distress. For example, New Jersey’s credit rating has been reduced several times by each of the major rating agencies over the past seven years,5 with the result that New Jersey has had higher borrowing costs for public improvements and prudent refinancing of existing debt. The state’s fiscal status has deteriorated over time; indeed, one recent study of states’ fiscal solvency ranked New Jersey 50th in the nation.6

Despite the constitutional requirement of a balanced budget, year after year New Jersey has achieved the appearance of balance by jeopardizing its economic future – deferring billions in pension obligations, skipping needed infrastructure repairs, and shortchanging economic drivers such as higher education.

It is simplistic to argue that a path forward for New Jersey can be built on spending reductions alone. In fact, most spending by New Jersey and other states is devoted to two areas in which the state's flexibility is limited: K-12 education and providing health coverage through Medicaid.

Reduction in Medicaid spending is limited because the federal government requires states to provide a basic set of benefits. Moreover, under the joint federal-state arrangement for funding Medicaid, each dollar that the state cuts would result in the loss of a dollar of federal assistance. Similarly, New Jersey Supreme Court decisions in the Abbott vs. Burke cases7 limit the state’s ability to significantly cut support for public schools. And, even if such reductions for K-12 education were possible, they would have adverse implications for the state’s future economic development and overall quality of life.

In short, New Jersey has no choice but to confront each of its substantial financial problems head on, with a focus on what best serves the long-term public interest.