In some ways, making sure New Jersey is a home for good jobs and offers families a secure future is a matter of effective matchmaking. Employers need to find qualified, well-trained people, and people need to find jobs. This issue looms large throughout the state. It affects communities where people struggle to get by, some of them needing the training in skills and job readiness that are prerequisites for meaningful employment. It also affects people who had the skills to make a good living, only to see their jobs disappear.

Achieving the match is made difficult by the antiquated nature of New Jersey’s workforce-training infrastructure.

Yesterday’s jobs are not today’s—and today’s jobs are not tomorrow’s. The increasing volatility of the labor market places a premium on improving one’s “human capital” to meet employers’ needs. Rapid changes in technologies and business practices exacerbate current trends and show the need for New Jersey to do a better job of helping people get the training and support they need to get work that supports a family.

One big target for such assistance is the nearly 75,000 New Jerseyans who, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, have not been able to find work after months or even years of joblessness. Many of the long-term unemployed have become part of the “missing labor force.” In fact, more than three in 10 of New Jersey’s unemployed have not been able find a job for more than six months. New Jersey’s rate of long-term unemployment is among the highest of any state, and significantly higher than the national average of 23.3%.31

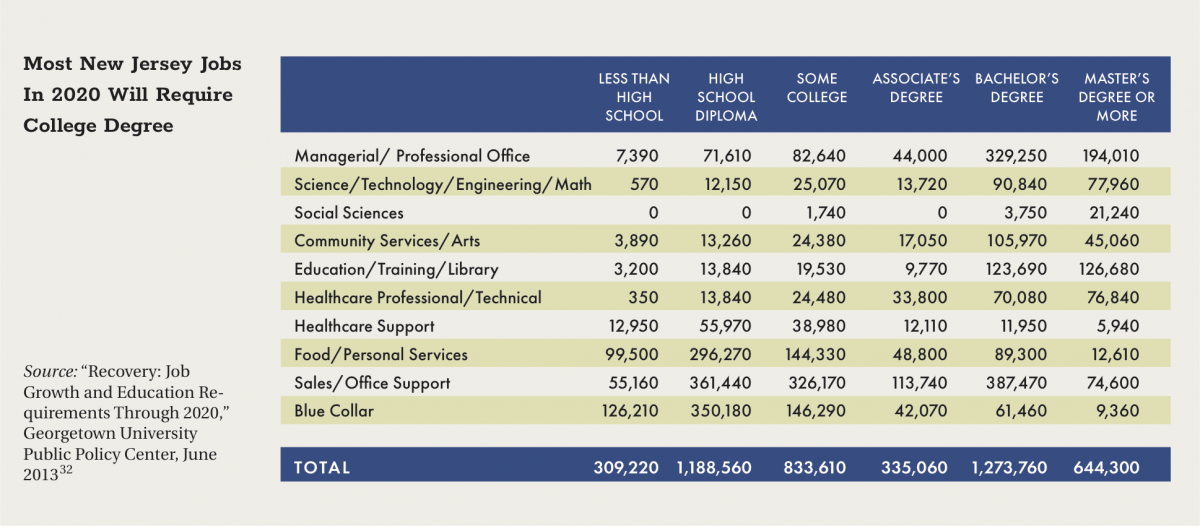

Given such chronic problems, and their impact on the state’s competitiveness, New Jersey needs strategies for delivering far more robust and effective education and training. Educational attainment levels in New Jersey remain far below what most workers need to obtain good, family-supporting jobs. According to U.S. Census data from 2015, 10.9% of New Jersey’s residents have not earned a high school diploma, the minimum requirement for nearly every job today. While 42% of New Jersey residents have earned a postsecondary credential, far more New Jersey job applicants in the coming decades will need at least some postsecondary education to obtain a good job.

INCREASING SCHOOL COMPLETION RATES

One place to start is increasing high school and college completion rates. According to the New Jersey Department of Education, the state average high school graduation rate is 85%. However, graduation rates are far lower in several large urban school districts, including Camden (70%), Newark (73%), and Atlantic City (76%).33

Graduation rates from state colleges and universities also vary widely. While 73% of College of New Jersey students and 54% of Rutgers University students graduate within four years, less than a tenth of students complete their degrees in that time frame at New Jersey City University, and less than a fifth graduate in four years at Kean University or William Paterson University. At community colleges, the overall completion rate for students seeking an associate’s degree is less than one in five after three years of enrollment. And, thousands of students who did not finish their postsecondary education need assistance to complete their course work in class or online.34

RECOMMENDATION

Make greater efforts to increase high school and college completion rates in order to prepare young people for good jobs in the 21st-century economy.

Completing degrees in a timely manner is good for students because it helps lower their debt burden, and it is good for New Jersey’s economy. Completion rates have increased dramatically in several states where higher education institutions focus on such structural changes as making remedial education more available and providing additional guidance for students throughout their college careers.35

Expand state financial aid eligibility to undocumented students.

Undocumented young people face additional challenges in their pursuit of college and careers. Laudable policy changes have enabled undocumented students to pay in-state tuition at New Jersey’s public colleges and universities. But too many are still kept from success because they are prohibited from receiving state or federal financial aid. Eight states allow aid for undocumented students, helping them contribute productively to their communities’ economic well-being.

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

Public workforce development efforts, funded primarily by the federal government and administered at the state and local levels, are crucial for unemployed job seekers, many of whom lack postsecondary education credentials. These efforts help people achieve basic literacy and math skills, and provide skills training and postsecondary education that lead to industry-recognized credentials in occupations ranging from auto mechanics to robotic machine technicians.

At a time when the job market brings unprecedented demands for better-qualified labor, federal funding for workforce education, training, and employment assistance

has diminished. After an increase during and immediately after the 2008 recession, funding dropped below pre-recession levels. Because New Jersey did not make up for the funding losses, fewer people can get services, and the quantity and quality of those services have declined.

RECOMMENDATION

As federal support wanes and the state’s fiscal crisis continues, focus resources on chronically unemployed youth, low-paid workers, people with disabilities, veterans, and the long-term jobless.

Pennsylvania sets a good example by setting aside 70% of funding from the federal Workforce and Opportunity Act for these “hardest to serve” groups. Adopting this focus, New Jersey public workforce agencies should coordinate with other providers of support services to develop individual employment plans aimed at increasing opportunity.

TYING UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE TO TRAINING

Through the state unemployment insurance system, New Jersey can provide valuable help to make joblessness as brief as possible. In New Jersey, as in most other states, UI provides six months of support to the unemployed except part-time workers and those who come in and out of the labor market frequently.

RECOMMENDATION

Reform unemployment insurance so all recipients receive job-search assistance and coaching during the early stages of joblessness.

The current setup misses out on key opportunities.

RETHINKING ON-THE-JOB TRAINING

In decades past, when workers remained with employers for most or all of their careers, employers provided most of the necessary skills training. As layoffs become more common due to downturns in the economy, corporate restructuring, and technological change, fewer companies are willing to take responsibility for employees’ career development.

Apprenticeships and management training programs are disappearing rapidly, and companies in competitive job markets demand that new employees come prepared to “add value” as soon as they are hired.

In short, responsibility for workforce preparation today rests more with individual workers, many of whom lack the skills and resources to navigate a web of occupational requirements and training programs. Rapid technological innovations, constant organizational restructuring, and ongoing market shifts transform job functions and requirements every few years, not every few decades. Workers and educational institutions alike find it difficult to anticipate and train for this rapidly changing labor market.

RECOMMENDATION

Focus workforce development programs on on-the-job training for industry-certified credentials.

On-the-job training includes partial, temporary wage subsidies, usually 50% of wages for six months—which enables companies and the government to invest in advancing workers toward stable employment. Under such a strategy, employers provide training that meets their specific needs, and unemployed or underemployed workers get a pathway to a job with good wages. In turn, people enrolled in such programs can earn while they learn without paying tuition. On-the-job training can be developed in a wide variety of businesses, from entry-level health services to complex manufacturing and technology work.

Make public funding of specific community college-based training for the unemployed available only when the curriculum leads to attainment of a credential that is endorsed by groups of private employers and, as such, is portable from one company to another.

This would go beyond existing law by requiring community colleges and workforce training providers getting government support to provide certifications or course credits that can lead to a more advanced certification or degree acceptable to programs in the same field. Such “stackable” credentials help people achieve skills they can use to advance in their field. Generally, those credentials are transferable from one employer to another within the same industry and help promote career mobility. To help them implement this requirement, colleges and training providers should receive additional funding for assistance and support.36

Give public money to customized training designed for a specific firm only when the costs are principally borne by the company that intends to hire those who complete training.

This change will lead to a more effective use of funding now available under the Workforce Development Partnership Program. When the state provides training assistance to companies that are moving to New Jersey or retraining their in-state workforce, the companies should bear more than half the cost of the training.

MOVING ONLINE

Today, Internet-based software platforms can deliver workforce development and reemployment services more efficiently than the One-Stop Career Centers found in nearly every New Jersey county. Unemployed persons are directed to go to these centers for job search assistance or to obtain training. This approach is inadequate in a society where services are increasingly delivered online and available 24/7 on computers, laptops, tablets, and smartphones.

Job seekers and students need timely access to ongoing career management supports, industry-recognized training programs, and accurate information about skill needs and occupational requirements. Advances in information technology enable customization of such services more quickly and at a lower cost than in the past. User-friendly software developed by a number of private firms can help job seekers to complete online applications, optimize their resumes, and prepare for interviews from smartphones or any computer with broadband Internet access.

RECOMMENDATION

Expand and enrich high-quality, Internet-based platforms to deliver workforce development and reemployment services.

This first step in a long-overdue overhaul of state information technology systems would include selecting and implementing “best in class” workforce development software, acquiring the hardware, and hiring the staff to support these new technologies. A good model is the OpenSkills API released by the U.S. Department of Labor and the University of Chicago’s Center for Data Science and Social Good. It combines information about jobs, skills and training, and potential incomes, which can help policymakers, job seekers, and employers better understand the needs of the 21st-century workforce.37

This is a bigger issue than just workforce development systems. The IT systems New Jersey has in place throughout state government need to be updated for flexibility, user-friendliness, and consistency with what the public has come to expect in commercial and other applications.