The barriers that far too many New Jerseyans face in trying to obtain jobs—particularly those that pay enough to support a family—must be overcome for the state’s economy to reach its potential. For many, the recession is permanent. Those of prime working age (18 to 59) often face significant, structural causes of unemployment. Helping them will require removing obstacles that reflect employer hiring practices, societal attitudes, and legal requirements. For individuals, these obstacles include disabilities, involvement in the criminal justice system, family obligations, and discrimination.

No racial, ethnic, or demographic group in New Jersey is immune to economic difficulties. Young people—especially males of color—face particularly significant challenges in gaining a foothold in the labor market.14 Because of income inequality and housing discrimination, youth of color often live in economically depressed, racially segregated neighborhoods with few prospects for work. Many young people from families struggling to make ends meet lack the networks and relationships to find job leads and internship opportunities—connections that middle-class and more-affluent New Jerseyans, who are more likely to be white, take for granted. Racial discrimination is also implicated in erecting barriers to employment. A 2013 study of job-seekers in the New Jersey labor market found that, after controlling for all other factors, at least one third of the raw wage gap between blacks and whites was due to racial discrimination.15

WAGE LEVELS

Following passage of a 2013 ballot referendum raising New Jersey’s minimum wage above the national level and establishing subsequent automatic annual increases pegged to inflation, the minimum wage in the state stood at $8.38 per hour in 2016 and rose to $8.44 in 2017.

With a minimum wage exceeding the federal rate of $7.25 per hour, and with the 2016 enactment of an increase in the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit for families where a parent works at low wages, New Jersey offers modest support for workers at the lowest end of the wage scale. Given that more than 80% of poor adults in New Jersey are working, this is a valuable strategy to improve the economic prospects for those in jobs that pay too little for a family to afford necessities. However, more support is needed.

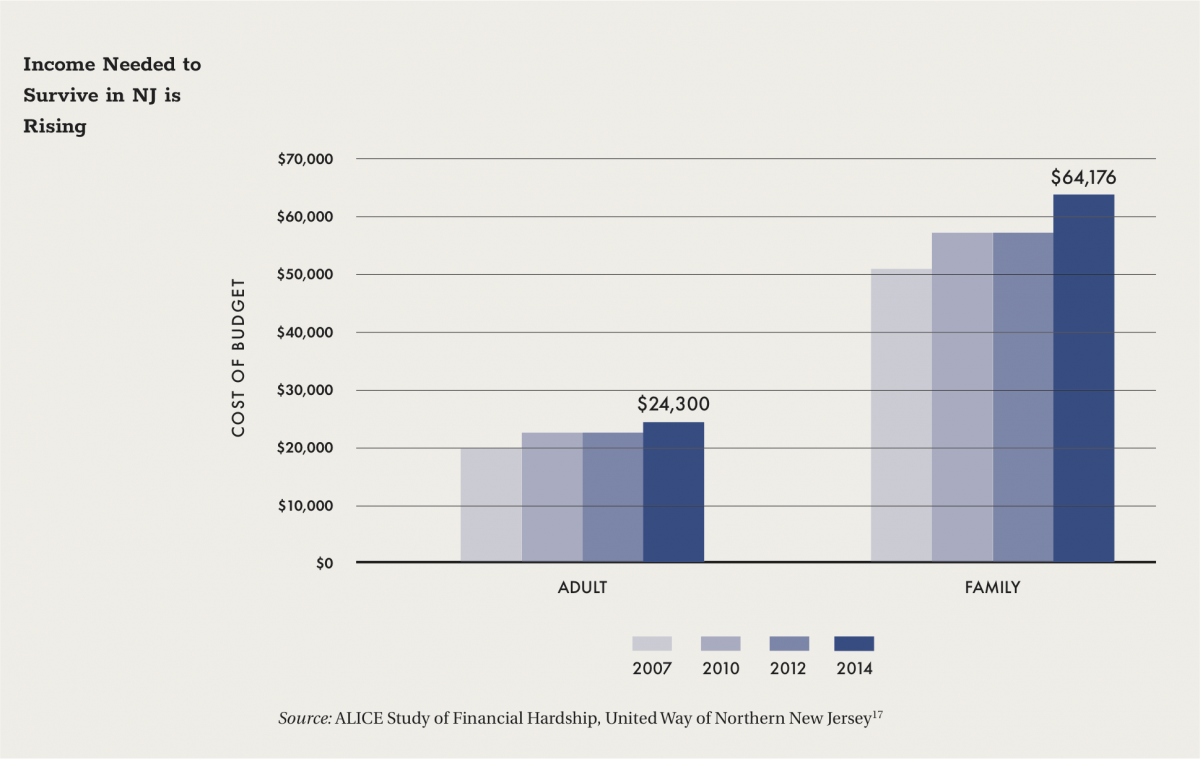

The United Way of Northern New Jersey has estimated a single adult in New Jersey needs to earn $13.78 an hour to meet basic needs, and $19.73 per hour for “better food and shelter, plus modest savings.”16 Put another way, two people would each have to work about 70 hours a week at minimum wage to meet the $64,176 annual “survival budget” for a family of four.

RECOMMENDATION

Make the minimum wage in New Jersey a “livable wage” by mandating a pay level linked to the cost of meeting basic needs.

Too many New Jerseyans are paid too little to support a family and build a future.

HELPING TIPPED WORKERS

Meanwhile, well over 100,000 New Jersey working men and women are legally paid less than the minimum hourly wage because, under state law, people whose jobs involve tips are guaranteed only $2.13 an hour, the lowest in the Northeast—a rate unchanged since 1989. Employers are supposed to make up the difference for workers who do not make enough in tips to reach minimum wage, but that does not always happen. The average tipped worker in New Jersey makes less than half the pay of other workers and is far more likely to lack health insurance.

RECOMMENDATION

Eliminate a separate minimum wage for tipped workers.

This would boost the standard of living for many hardworking people and simplify labor regulations. In the seven states where tipped workers receive minimum wage, employment growth in the leisure and hospitality sector over the past 20 years outpaced states where tipped worker are paid a subminimum wage.18

ECONOMIC SECURITY

Having a job in New Jersey does not always mean having the right to paid sick leave. Over 1 million people have mostly low-paid jobs with no paid sick time. They must forfeit their pay—and risk losing their jobs—if they or a family member are sick.

RECOMMENDATION

Require that all employees have the right to accumulate a specified number of earned sick leave days per year and be allowed to take time off with pay.

Seven states and numerous municipalities, including 12 in New Jersey, require employers to grant earned sick days.

New Jersey in 2008 became the second state to adopt family leave insurance, a system where working people have a small portion of their pay set aside so they still receive part of their salary when they take time off to be with a new child or sick family member. For many people, however, the amount they would receive is too low for them to take advantage of the program. Reforms would enable more people to support their families at important times. As the law stands now, family leave can be granted for six weeks during a 24-month period, with compensation at two-thirds of an employee’s regular pay.

RECOMMENDATION

Strengthen family leave by increasing the current two-thirds wage replacement, including job protections for people taking leave, increasing paid leave to a maximum of 12 weeks, and improving outreach efforts so more people are aware of their rights.

Family leave in New Jersey is funded entirely by mandatory worker contributions. A small increase in the amount withheld—now about $26 a year—would cover these reforms.

Federal and state Earned Income Tax Credits help low-paid working families afford necessities. New Jersey has been a leader in expanding the size of this tax credit as a share of the federal tax credit, with one key exception: families not raising children in their home are ineligible for the state EITC.

RECOMMENDATION

Make the state Earned Income Tax Credit available to families not raising a child in the home.

The state and federal EITCs help reward work and build assets while off setting state and local taxes that fall hardest on those with the lowest incomes. Extending New Jersey’s EITC to working people who are not raising a child would help the state economy.

HELPING PEOPLE WITH CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS

One in five residents of New Jersey has been involved with the criminal justice system. Employment barriers affect many of them.

In 2016, there were 94,315 New Jerseyans in prison or on parole or probation. Here again, every racial and ethnic group was represented. But slightly more than half (47,470) were African-American, the large majority of them male.19

Ultimately, 95% of the incarcerated population is released—about 10,000 each year in New Jersey.20 In almost every case, these men and women return to society during their prime working years to seek jobs, and employers are often unable or unwilling to give them a chance. The formerly incarcerated must overcome barriers to employment beyond weak networking and the structural racism that leads to disproportionate criminal justice system involvement among people of color.

With the 2015 passage of New Jersey’s Opportunity to Compete Act (OCA), also known as the “Ban-the-Box” law, employers cannot ask about an applicant’s criminal history until after the first interview; nor can they use expunged or pardoned convictions in making hiring decisions. New Jersey is one of only seven states applying this prohibition to private-sector employers.21 Recognizing that having a job facilitates re-entry, the OCA is an important first step in helping people with criminal convictions find work. More should be done.

RECOMMENDATION

Strengthen the law to permit employers to inquire about an applicant’s criminal history and complete a background check only after making a conditional offer of employment. In addition to government enforcement of this law, there should be a private right to sue to facilitate enforcement.22

To rescind a conditional job offer, employers should be required to provide a written explanation to the applicant of why the criminal history makes him or her ineligible for the position, and provide the applicant with an opportunity to respond. New Jersey also should examine and publicly report on denials of employment based on criminal convictions across racial and ethnic groups in the state.

ENDING WAGE THEFT

Throughout the nation, working men and women lose millions of dollars a year to wage theft. The practice takes such forms as paying for fewer hours than worked, failing to pay for overtime work, and paying less than the minimum wage. Workers in fields including health and home care, trucking, and food service are among the most vulnerable, and undocumented immigrants are in the most precarious position. They often hold back on trying to collect what they are due for fear of retaliation. And the ne of up to $500 that employers in New Jersey face for violations is too small to be a deterrent.

RECOMMENDATION

Strengthen protections against wage theft and increase penalties for employers.

A comprehensive approach would include:

- imposing higher fines;

- extending the statute of limitations’ two-year period for victims to seek restitution, to increase the likelihood that a worker, who risks retaliation for reporting wage theft, will have a new job before making the complaint;

- holding employers and labor contractors jointly responsible for violations; and

- expanding efforts to inform people of their workplace rights and how to report violations.

STRENGTHENING THE SAFETY NET

Hundreds of thousands of New Jersey residents with extremely low incomes qualify for public assistance that provides relatively meager support. Approximately 16,000 parents of dependent minor children receive cash welfare assistance of no more than $424 per month for a maximum of five years through federal-state Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). An additional 17,000 adults receive General Assistance benefits of no more than $210 per month.23 Only half of the adults whose incomes qualify them for this assistance can work at all; many have mental or physical health disabilities that raise severe barriers to getting a job. In addition, around 450,000 New Jersey households receive support from the federally funded Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), otherwise known as food stamps. The majority are families where at least one adult is employed—at low wages.24 Among these public-support recipients are unemployed residents available for and capable of full-time work. For instance, approximately 11,000 “Able Bodied Adults without Dependents” (ABAWDs) are required to participate in job search, job training, or employment as a condition of receiving SNAP.

RECOMMENDATION

Automatically increase levels for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and other forms of public support yearly to reflect the rising cost of living.

Increased support also should take the form of greater child care and transportation assistance, which can be crucial in helping people obtain well-paying jobs.

PRIVATE-SECTOR ENGAGEMENT

Recognizing the important role the private sector can play in strengthening New Jersey’s economy, leaders of large corporations in the state often engage in public-awareness campaigns and other voluntary actions to advance social justice. One example is the “Fair Chance Business Pledge,” in which 185 employers made a commitment to eliminate job barriers for people with past criminal convictions. In addition, several leading New Jersey businesses have joined concerted efforts to promote the hiring of persons with disabilities.

RECOMMENDATION

Aggressively promote e orts to enlist more business leaders in adopting the “Fair Chance Business Pledge.”

Voluntary coalitions targeted at employing people who have been convicted, people with disabilities, and youth of color from economically struggling families could improve the visibility of these groups and strengthen the case for their employment.

Encourage corporate CEOs to form a high-pro le working group charged with developing strategies to hire more women and people of color, and to increase purchasing from small businesses owned by women and people of color.

Bringing to bear the collective influence of state corporate leaders would provide impetus valuable to achieving growth in hiring and in small business development.

PROMOTING FULL ECONOMIC PARTICIPATION

Getting to work in most parts of New Jersey requires a car. Indeed, it is difficult to get through life without driving. A car is necessary to get to work, pick up children, go to the store, and do everyday tasks. But undocumented immigrants, people recently released from incarceration, and others who do not have enough documented roots to meet the Motor Vehicle Commission’s identification requirements cannot get licenses, and driving without a license creates perpetual anxiety and vulnerability. A traffic stop, accident, or breakdown that would be a headache for license holders becomes a nightmare for others. New Jersey’s policy on this issue turns law-respecting residents into scofflaws by definition, and it needs to be changed.

RECOMMENDATION

Expand availability of New Jersey driver’s licenses to all state residents who meet age and skill qualifications, regardless of immigration status; include strong privacy protections for personal information.

These licenses would not be valid for such purposes as receiving government benefits, work authorization, or air travel.

Washington, D.C., and 12 states allow undocumented immigrants to drive. Doing so in New Jersey would enable 460,000 of the state’s estimated 525,000 undocumented immigrants to drive legally.25 With licenses, more New Jersey residents could contribute to the state’s economy. And New Jersey’s roads would be safer because there would be fewer uninsured and unlicensed drivers. In addition, the state could collect an estimated $12.2 million to $16.6 million in license and registration fees.26

DO NOT LET PARKING FINES BE BARRIERS TO JOBS

People unable to pay accumulated parking fines can have their driver’s licenses suspended. By taking away the right to drive, the Parking Offenses Adjudication Act hinders the ability of residents to work; license suspensions can lead to job loss and less income.27

RECOMMENDATION

Repeal the state Parking Offenses Adjudication Act to help people, particularly those with low incomes, maintain full access to employment opportunities.

Basing the availability of a driver’s license on being able to pay a fine effectively denies the right to drive to low-paid people who struggle to make ends meet.