Fourteen years ago, an Urban Institute report (supported by The Fund for New Jersey) painted a bleak picture of available assistance for formerly incarcerated people as they sought to reenter society after incarceration.101 In the last decade, New Jersey has taken significant steps to create more opportunities for formerly incarcerated people through the passage of legislation hailed as a “model for the rest of the nation.”102 Also, we have seen the creation of nonprofit organizations dedicated to helping formerly incarcerated people.103

Yet, the benefits of eliminating mandatory minimums, reducing the severity of custodial sentences, and allowing prisoners to earn sentence reductions through commutation and jail-time credits will be substantially undermined if former prisoners are unable to reintegrate into society. After offenders are released from incarceration, they need to secure stable housing, a job, and health care to fully transition back to their families and into their communities. The collateral consequences of many criminal convictions in New Jersey work against those goals, leaving ex-inmates with few options and funneling many of them back into New Jersey’s prisons and jails.

MINIMIZING THE COLLATERAL CONSEQUENCES OF A CONVICTION

Former prisoners face daunting barriers to successful re-entry. In searching for stable and affordable housing, they must contend not only with the high costs faced by all New Jerseyans who struggle to make ends meet, but also with municipal housing authorities that may impose eligibility restrictions based on criminal history,104 and private landlords who may demand background checks and disqualify those applicants involved with the criminal justice system.105 When it comes to employment, former prisoners, particularly those convicted of drug crimes and other offenses under the category of “moral turpitude,” are barred by law from many positions, from public employees106 to firefighters107 to insurance adjusters.108 Many former prisoners must also deal with a lengthy driver’s license suspension that serves as a restriction on their ability to find and maintain employment.109

These consequences only add to the difficulties former prisoners experience in obtaining substance-abuse treatment, education or vocational training, and even cash assistance under certain public benefits programs.110

RECOMMENDATION

Reduce barriers that former prisoners face, by, among other things, providing transitional housing, eliminating unnecessary employment restrictions and driver’s license suspensions, and funding health care, educational and vocational programs, and providing other resources.

An Interagency Reentry Council, reporting to the governor, should be established to ensure maximum effectiveness of reentry initiatives.

EXTENDING EXPUNGEMENT TO MORE NEW JERSEYANS

Expungement makes the records of criminal convictions inaccessible for most purposes, mitigating the consequences of involvement with the criminal justice system.111 Several provisions of New Jersey’s expungement statute, however, unduly restrict eligible formerly incarcerated people. For example, many first- and second-degree nonviolent drug convictions cannot be expunged,112 and the waiting periods that apply (10 years for a crime, and five years for a disorderly persons offense113) are so long—longer than those in other states114—that the benefits are often illusory. In addition to shortening waiting periods, common-sense reforms would include simplifying the process to reduce the time and expense involved in applying for expungement115 and making the expungement of non-conviction records, such as dismissals, automatic under most circumstances.116

RECOMMENDATION

Make expungement more widely available in New Jersey by permitting multiple nonviolent first- and second-degree drug offenses to be expunged, reducing the lengthy waiting periods before expungement can be requested, and enacting provisions that enable longtime non-recidivists to “wipe the slate clean” by expunging their entire criminal records.

AVOIDING DEPORTATION

Criminal convictions, even for minor state crimes, trigger automatic deportation. Prior convictions also can bar otherwise qualified green card holders from becoming U.S. citizens.

RECOMMENDATION

The governor should create an advisory board to recommend cases for his or her consideration in granting pardons to people facing serious immigration consequences due to their criminal records.

Previous governors in Maryland and New York have made frequent use of their pardon power to vacate old or minor criminal convictions for lawfully residing immigrants117 and, recently, the governor in New York used his pardon power to give a longtime resident the chance to re-open his deportation case. An advisory board would serve law enforcement objectives while minimizing the unintended harsh consequences of minor criminal convictions. The board, in appropriate cases, could enable more lawfully residing immigrants to remain with their families and remove potential obstacles to pursuing citizenship.

RESTORING THE RIGHT TO VOTE

States vary in the extent to which they deny criminal offenders one of American citizens’ most basic rights. The spectrum goes from two states that let prisoners vote by absentee ballot to 12 that deny the right to vote even to offenders who have fulfilled all their obligations to the criminal justice system.118 New Jersey is among the more restrictive: no one in prison, on parole, or on probation can vote.

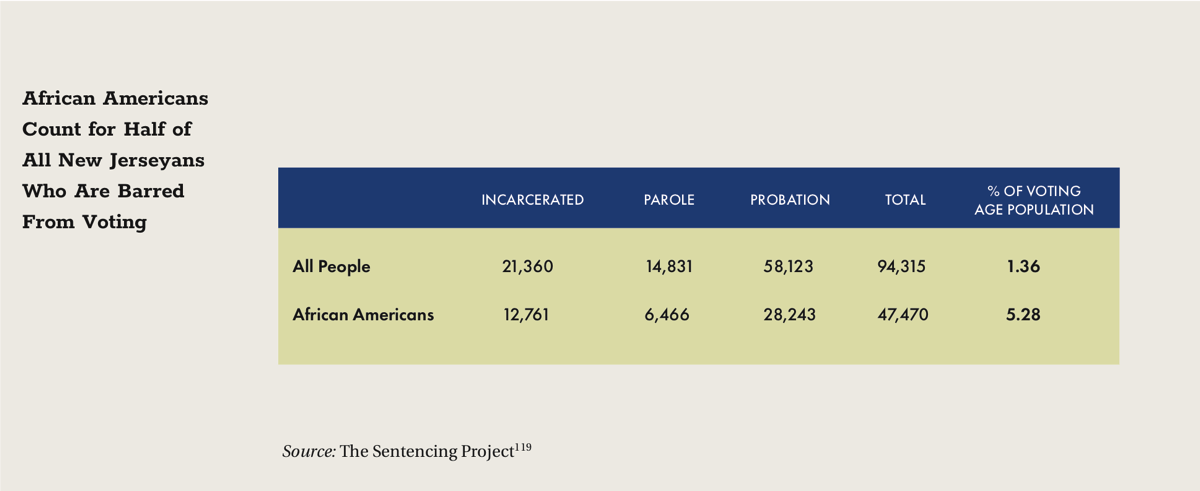

In a state where African Americans make up such a disproportionately large share of the incarcerated, denial of voting rights has broad implications.

More than 5% of the African American population of voting age is barred from voting in New Jersey: African Americans count for half of all state residents disenfranchised. The percentage of those barred in New York and Pennsylvania, by comparison, is less than 50% of those barred in New Jersey.

RECOMMENDATION

New Jersey should not deny criminal offenders the right to vote.

The state should join Maine and Vermont in allowing prisoners as well as people on parole or probation to vote. Allowing prisoners to vote would put New Jersey in the vanguard of reform and would constitute a major step toward reducing racial inequity in the criminal justice system.