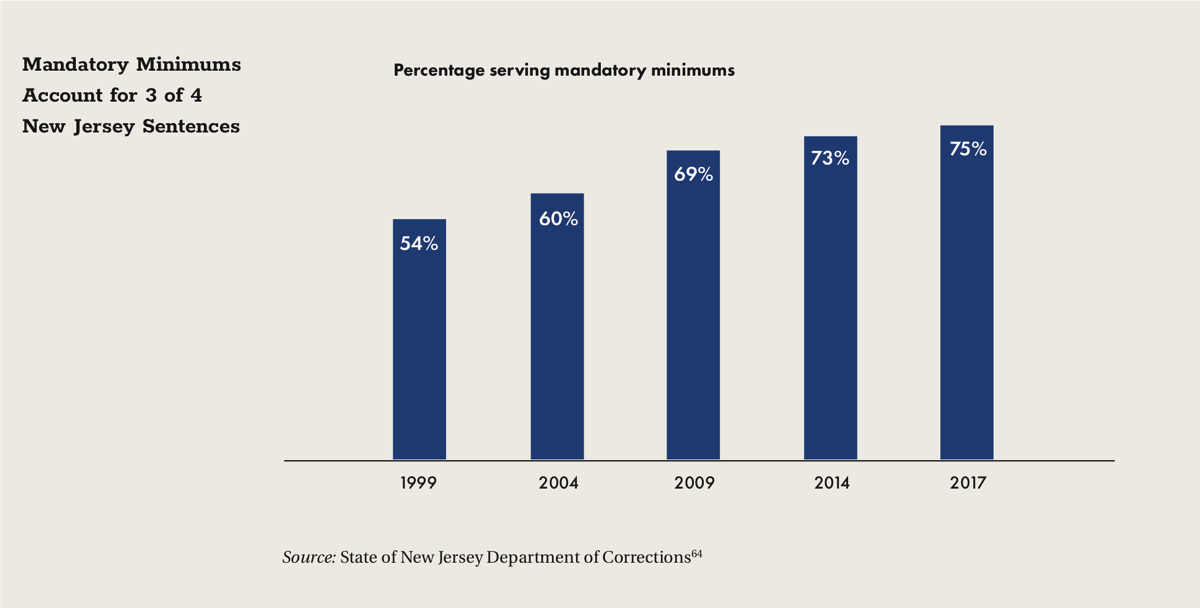

Two sentencing policies have contributed most to the growing number of people incarcerated in New Jersey over the past four decades: longer sentences and severe mandatory minimum sentences.61 Not only do we have more people in prison, but they are also confined for longer periods of time. In 1982, 11% of New Jersey’s 7,990 prisoners were serving mandatory minimum terms.62 Today, 74% of New Jersey’s 20,489 prisoners —more than 15,000 people—are serving mandatory minimum sentences.63

CURBING USE OF MANDATORY MINIMUM SENTENCES

Under mandatory minimum sentencing, judges lack discretion to reduce the time to be served below a specified minimum period.65 Further, prisoners serving mandatory minimum sentences are ineligible for parole, or credit for work or good behavior, during the minimum term.66

Although mandatory minimums suggest a tough-on-crime stance, they are often criticized as both ineffective at reducing crime and too expensive, increasing mass incarceration without a benefit to society.67 As leading sentencing scholar Michael Tonry has explained: “The evidence is clear that mandatory penalties have either no demonstrable marginal deterrent effects or short-term effects that rapidly waste away.”68

Opposition to mandatory minimum sentencing is not limited to academics and political liberals. Many jurists and conservative commentators have criticized mandatory sentencing requirements. For example, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy has said: “I’m against mandatory sentences. They take away judicial discretion…”69 Justice Stephen Breyer has written: “In 1994 Congress enacted a ‘safety-valve’ permitting relief from mandatory minimums for certain nonviolent, first-time drug offenders. This, in my view, is a small, tentative step in the right direction. A more complete solution would be to abolish mandatory minimums altogether.”70 Grover Norquist, president of the advocacy group Americans for Tax Reform, has testified that “[t]he benefits, if any, of mandatory minimum sentences do not justify this burden to taxpayers.”71

Recognizing the need to address the rising financial cost of incarceration, over the past decade several states have eased many of their mandatory sentencing laws. Michigan, in 2003, repealed almost all mandatory minimums for drug offenses. After the repeal, during the period from 2006 to 2010, the state’s prison population fell 15%, spending on prisons declined by $148 million, and both violent and property crime rates declined. Rhode Island, in 2009, repealed all mandatory minimum sentencing laws for drug offenses. Since then, its prison population has declined by 12% and the state’s crime rate is down by several percentage points. And South Carolina, in 2010, eliminated mandatory minimum sentences for first convictions for simple drug possession.72

New Jersey is not among the states that have taken steps to reduce mandatory sentences. Of the more than 100 changes that New Jersey made to its sentencing scheme from 1979 to 2007, 39 involved new or harsher mandatory minimum sentences and none eliminated or reduced such sentences.73 In the years since 2007, the Legislature reduced a mandatory minimum penalty only once and raised mandatory minimums several times.74 Today mandatory minimum sentences exist in New Jersey for murder75 and other crimes of violence,76 offenses involving firearms77 and drugs,78 and official misconduct,79 among other crimes.80

RECOMMENDATION

Eliminate mandatory minimum sentences in New Jersey.

Judges should be allowed to impose harsh sentences when appropriate, but should also have the discretion to avoid unnecessarily long incarceration.

We should eliminate mandatory minimums for nonviolent offenses without further delay. We should move quickly to review sentencing guidelines to end mandatory minimums as appropriate across the system.

RECALIBRATING BASE SENTENCES TO REFLECT THE LOSS OF PAROLE AND EARLY RELEASE CREDITS UNDER CURRENT LAW

A most important consideration for those affected by the criminal justice system— defendants and victims alike—is the actual amount of time a defendant will serve, taking into account credits, parole, and other opportunities for early release.81

In the 1990s, when the federal government provided incentive grants for prison construction to states that passed laws requiring certain serious violent offenders to serve at least 85% of their sentences prior to release,82 New Jersey responded by passing the No Early Release Act (NERA)83 and actual prison terms lengthened considerably. Take, for example, someone charged with an armed robbery and given a 10-year sentence. Previously, the term served before parole eligibility had been three years and four months. After NERA, the term served before parole eligibility was reset at eight years and six months, more than doubling the previous requirement. Despite significant increases in required time served, New Jersey has never adjusted the base terms for most offenses. Indeed, whenever New Jersey has changed base terms by altering the degree of the crime associated with certain behavior, the degree has been raised and the base terms have increased.84

RECOMMENDATION

Adjust criminal sentences to reduce the base term for criminal sentences for which early release is prohibited.

ESTABLISHING A SENTENCING REFORM COMMISSION

In 2004, recognizing that new criminal offenses had been added to the code and that penalties for many existing offenses had been increased, the Legislature decided to re-examine whether the sentences for these offenses were fair and proportionate. The result was a Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing.85

That commission operated until 2009, when it was replaced by a Criminal Sentencing and Disposition Commission.86 The new commission’s objective was to thoroughly review criminal sentencing and consider recommendations for revisions with a goal toward “a rational, just and proportionate sentencing scheme that achieves to the greatest extent possible public safety, offender accountability, crime reduction and prevention, and offender rehabilitation while promoting the efficient use of the State’s resources.” The commission was also tasked with considering issues of disparity in the criminal justice process, including sentencing and racial and ethnic disparities.87

The Criminal Sentencing and Disposition Commission has never met, and no members have been appointed.88 Without sufficient information about the realities of sentencing practices, the public and policymakers cannot make reasonable decisions about reform.

RECOMMENDATION

Appoint members to the Criminal Sentencing and Disposition Commission so that it can fulfill its statutory duty to examine New Jersey’s sentencing scheme.

Set up a comprehensive system for reporting detailed information on sentences served and the resulting financial costs.

The Department of Corrections should be required to publish data on sentences served, broken down by offense, county, race, ethnicity, gender, and age. Data regarding the cost of incarceration and alternatives to incarceration also should be made readily available.

Ensure that some members of the Criminal Sentencing and Disposition Commission have expertise in immigration law. The Commission should reconsider the classification of certain crimes in order to eliminate immigration consequences, i.e., deportation.

Any examination of sentencing in New Jersey must also include consideration of the ways in which criminal law interacts with federal immigration law to create anomalous and undesirable results. Immigration law is particularly unforgiving. Criminal convictions—even for minor state crimes—often trigger automatic deportation. For example, being convicted of a non-serious New Jersey crime, such as shoplifting in the fourth degree, could get a green card holder deported simply because the charge carries a possible sentence of more than one year.