New Jersey is one of the most diverse states in the nation but our schools do not reflect our state demographics. Instead, many districts reflect population concentrations of poor and minority students while other districts serve primarily wealthy and white students. Even within districts that have more diverse student bodies overall, racial disparities can be found among the district schools. The achievement gaps between and within districts reflect deep-rooted divides.

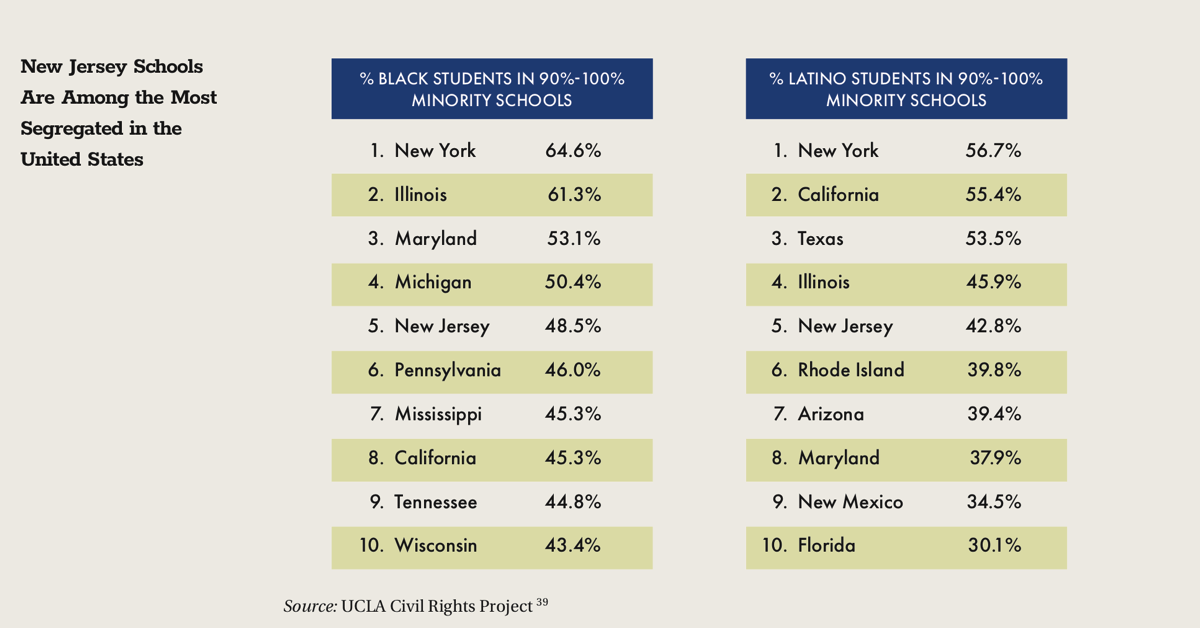

Our state’s record is paradoxical: New Jersey has the nation’s strongest constitutional and legal framework for integration of the public schools35 and is among those states that are the most segregated on the ground.

In 1947, New Jersey was the first state to adopt a constitutional provision that specifically prohibited segregation in public schools.36 State Supreme Court decisions in the 1960s and early 1970s established a strong legal framework for integration in public education and led to the creation of the Morris School District in the 1970s, merging the urban, lower-income, African-American Morristown district with the surrounding suburban, middle- and upper-income, mostly white Morris Township schools.

But few New Jersey towns seem inclined to follow Morris’ lead; indeed, in the 1990s and 2000s the state Supreme Court blocked school district efforts to alter regional configurations in ways that were expected to increase segregation. Despite these rulings, New Jersey’s schools are now among the most segregated in the country, with urban schools enrolling mostly African-American or Latino students, while suburban schools remain mostly white. In the 25 years between the 1989-90 and 2015-16 school years, the state’s proportion of “intensely segregated” schools (90% to 100% minority students) increased to 20.1% from 11.4%, and the proportion of so-called “apartheid schools” (schools where 99% of the student population is African-American or Latino) grew to 8.3% from 4.8%. Today, 27.2% of African-American and 14.5% of Latino students in New Jersey attend one of those apartheid schools.37

In the United States, as in New Jersey, poverty and racial isolation frequently occur together. In the 2015-16 school year, 76.9% of New Jersey students in intensely segregated schools were from low-income families compared with 37.6% statewide.38

Research demonstrates that segregation and concentrated poverty can have lasting, detrimental intergenerational consequences. Children whose families have lived in poor and segregated communities for two generations score, on average, eight points lower on problem-solving tests and seven points lower on reading tests than children whose families have lived in more affluent communities, a gap that is the equivalent of missing two to four years of schooling.40

Although New Jersey is one of the nation’s most diverse states, its residents face high levels of racial and socioeconomic segregation that persist because they are grounded in patterns of housing segregation. Because most New Jersey school districts conform to municipal boundaries and restrict school attendance to residents of the municipality, these housing patterns contribute to high levels of segregation across and in school districts.41

Segregated housing patterns in New Jersey and elsewhere are the result of policies such as redlining, which denied federally insured mortgages to residents of “hazardous” neighborhoods (neighborhoods where the local population was substantially non-white or poor). Other factors included restrictive covenants that limited home ownership in exclusive neighborhoods to white residents and discrimination by realtors and homeowners against potential buyers or renters who were people of color.42 In New Jersey, residential segregation was reinforced by exclusionary zoning codes that were described in 1975 in the state Supreme Court’s Mount Laurel I decision.43 These codes require larger lots for single-family houses and limit multifamily housing, thereby increasing occupancy costs and putting residency out of reach for lower income families.

The New Jersey Supreme Court’s groundbreaking Mount Laurel rulings in 1975 and 1983 required municipalities to use their zoning powers to promote, rather than restrict, opportunities to produce homes affordable to low-and moderate-income households.44 Mount Laurel II put teeth in the original doctrine and set the stage for the development and implementation of a fair share methodology that allocates housing obligations to municipalities based on their share of the region’s wealth, jobs/ratables, and capacity

for growth in accordance with the State Plan. But implementation was not consistent and had, until recently, stalled. Even today, municipal zoning codes limit housing opportunities for low- and moderate-income families throughout the state and encourage land use that is substantially more segregated and sprawling than it was in 1970.45

These dynamics create communities where poverty is concentrated, educational and economic opportunities are scarce, and upward mobility is limited—and where populations are often racially homogenous. Our entrenched system of local school districts, with attendance boundaries that follow the municipal boundaries, creates significant obstacles to advancing both educational equity and racial integration, goals enshrined in the state Constitution and buttressed by decades of court rulings. Moreover, the current structure contributes to building barriers between New Jersey’s diverse groups, diminishing a common sense of purpose and community. New Jersey can, and should, do better.

Enrollment in integrated schools benefits all children.46 Low-income fourth graders who attend economically integrated schools are as much as two years ahead of their low-income counterparts attending high-poverty schools.47 Students attending racially and socioeconomically diverse schools achieve higher test scores and better grades than peers attending high-poverty and segregated schools. Indeed, students attending diverse schools are more likely to graduate from high school and attend and graduate from college.48 African-American youth who spend five years in desegregated schools earn 25% more later in life than do those who never had that opportunity.49 And, those benefits accrue to the next generation: the children of parents who attended integrated schools have “increased math and reading test scores, reduced likelihood of grade repetition, increased likelihood of high school graduation and college attendance, improvements in college quality/selectivity, and increased racial diversity of student body at their selected college.”50

Integrated schools also benefit white students, offering varied points of view in classroom discussions and promoting critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Research demonstrates that “racially diverse schools are not linked to negative academic outcomes for white students” and bring longer-term life benefits: “Compared to racially isolated educational settings, racially integrated schools are associated with reduced prejudice among students of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, a diminished likelihood of stereotyping, more friendships across racial lines, and higher levels of cultural competence.”51

In New Jersey, however, school segregation persists.

There are options for promoting integration. Districts that are racially and socioeconomically diverse can draw school attendance boundaries in ways that mitigate in-district residential segregation. See, for example, redrawn boundaries in Princeton and Montclair school districts. In other settings, the state can encourage integration by developing magnet schools and inter-district choice programs designed to draw families voluntarily to more diverse schools.

MAGNET SCHOOLS

Magnet schools are able to draw students across traditional school district boundaries and usually have a thematic focus (such as science, mathematics, or arts) with unique programming that is “magnetic” enough to attract diverse families. These schools were developed during the 1970s to encourage voluntary desegregation. Whereas busing, the other major desegregation tool of the time, was used to move students to specific schools in order to reduce racial isolation, magnet schools offered families choice. According to the U.S. Department of Education, magnets were modeled after academically selective high schools, with one key distinction—testing and other academic indicators were not used to determine admission.52

Although magnet schools were intended to be non-selective, diverse, and innovative, they have evolved over time to include selective, less diverse schools not unlike the specialized schools that served as an academic model for the magnets. In New Jersey, for example, magnet high schools are among the state’s most distinguished educational institutions; according to U.S. News and World Report, seven of the 10 highest-performing schools in the state are magnets, most of them county technology academies where admission is based on grades and test scores.53 Although the success of the tech academies demonstrates that families will cross district lines to obtain enhanced educational opportunities, these schools are less successful as vehicles of racial and socioeconomic integration. Because their stringent admission requirements effectively exclude students from under-resourced elementary and middle schools, the magnets remain predominantly white and Asian, and enroll few students qualifying for free or reduced-price meals.

Magnet schools can, however, be used to advance diversity, as they have in Hartford, Connecticut. Like New Jersey, Connecticut is a geographically small, wealthy, and highly educated state that boasts some of the best and worst schools in the country; its excellent schools are mostly in affluent suburban districts while its lowest performing schools are concentrated in its low-income and majority-minority urban centers.

In 1996, responding to a case brought on behalf of urban schoolchildren, the Connecticut Supreme Court, in Sheff v. O’Neill, held that the Hartford public school students had a right to the same quality of education as students in the wealthy suburbs surrounding the city.54 The Court recognized that local school districts in a state where communities were segregated led to segregated schools (in 1991, 94.2% of the Hartford school district was made up of minority students, compared with 25.7% statewide). The Court directed the Legislature and governor to develop a plan for school integration in Hartford and its neighboring municipalities.

Since then, the plaintiffs, the City of Hartford and its school district, and the state have worked to desegregate Hartford schools through 45 host (City of Hartford) and regional (operated by the Capital Regional Education Council) inter-district pre-K-12 magnet schools that attract affluent suburban students to the city through thematic focus (science and technology, liberal arts, career readiness), unique resources (state-of-the-art media labs, tuition-free college courses, or internships), and free preschool. Hartford also uses an Open Choice program that provides Hartford students with access to suburban schools within the 22-district Sheff region.

Research has shown that Connecticut’s inter-district magnet schools have improved educational outcomes for Hartford students and led to better social interactions for all students that participate in the program. Compared with non-magnet peers, minority magnet students were “less likely to be absent,” “perceived more encouragement and support for college attainment,” and had more diverse groups of friends. White magnet school students were more likely to have minority friends than white non-magnet suburban students and all students were more likely than their non-magnet school counterparts to say that their school experience had helped them to better understand people from other groups.55

RECOMMENDATION

Require New Jersey’s existing magnet high schools to include metrics for a diverse student body in their admission decisions.

Develop additional magnet schools, as appropriate, that include diversity criteria.

INTER-DISTRICT SCHOOL TRANSFER

Inter-district school transfer allows students to attend schools beyond the boundaries of their home school district, giving families the ability to choose where their children go to school and challenging the notion that housing and education have to go hand in hand. Inter-district school transfer programs typically allow students to enroll in a receiving district with the cost of the school transfer incurred by the state (for tuition) and by the sending district (for transportation). In New Jersey, after the first year of participation the tuition dollars for participating students are transferred from the sending district to the receiving district.

In 1999, New Jersey piloted an inter-district public school choice option that was made permanent in 2010. Since then, that program has grown to serve approximately 5,000 students and 132 school districts. Because of increased costs (approximately $50 million) associated with program growth, in 2015-16 the number of students each district could accept was capped by the state even though there were students on the wait list.56

The New Jersey program has the potential to provide more students with an integrated education by giving students in majority-minority districts the opportunity to attend more integrated schools. As structured, however, sending districts are at a monetary disadvantage—they lose per-pupil state formula aid, which is sent instead to the receiving district. Moreover, New Jersey’s program is open choice, allowing families to rank schools based on preference with no consideration of how that choice might affect diversity within schools. Open choice programs have been demonstrated to increase rather than decrease segregation. Inter-district school transfers can be used instead to reduce racial isolation through the use of controlled choice, which assigns students so as to foster integration and, also, take parents’ preferences into account.57

RECOMMENDATION

Modify New Jersey’s Interdistrict Public School Choice program to include a controlled choice component.

Evaluate the controlled choice program to determine whether it is successful in reducing segregation.