A well-designed response to climate change would have the additional benefit of improving conditions for many in New Jersey who suffer disproportionately from environmental problems because of where they live.

The harm from unhealthy air, unsafe water, haphazard development, and projects such as incinerators and power plants is often worst in neighborhoods that are beset by social and economic stress and that do not have the clout of other communities to reject such projects. Air quality deteriorates in urban areas where ozone is trapped and concentrations of particulate matter are elevated; when temperatures rise, the air quality worsens further. Tap water for residents of many economically hard-pressed neighborhoods and communities of color comes from pipes more than 100 years old, which increases the potential for contamination. In many older homes and school buildings, children are exposed to unhealthy levels of lead, mold, and other indoor toxins—found in paint, in water drawn through lead pipes or copper plumbing soldered with lead, in furniture, even in older toys. The toxins can cause lasting brain injury, impairing children’s ability to learn and grow.

New Jersey’s urban areas also contain high concentrations of contaminated industrial sites, where cleanup efforts can be delayed for years—even decades—by litigation, the inability to identify a responsible party, lack of funding, or low priority on the remediation list. Some sites are simply paved over. Many urban parking lots, athletic facilities, and schools sit atop sequestered accumulations of toxic substances. One investigation found that 74% of New Jersey residents with incomes below the federal poverty line live within a mile of a contaminated site for which no cleanup plan exists.27

The responses to these communities’ environmental problems generally are site-specific or substance-specific. Poor air quality is treated as an air issue; poor water quality as a water issue; where to build a power plant is a siting issue. There is growing realization, however, that these multiple environmental problems need to be addressed together and to be framed in terms of the public health harms the pollutants cause.

Further, economically distressed neighborhoods and communities of color are too frequently located in places vulnerable to the effects of climate change: urban areas that experience unhealthy air quality when temperatures rise, severe flooding and contaminated water when rainfalls increase, plus inconvenience and worse when extreme weather disrupts the energy supply. More needs to be done to protect people in these communities.

RECOMMENDATION

Impose a moratorium on state regulatory approval or funding for any development that has not been screened to ensure that it is not adding to pollution burdens already imposed on economically struggling communities.

The requirement that state agencies take environmental justice into account would be strengthened by establishment of an Environmental Justice Advisory Council, whose responsibilities would include monitoring the cumulative impacts of development in communities over time.

In the current system, developers need show only that the harm from any one form of pollution does not exceed danger levels. With analysis of cumulative impacts, the multiple forms of pollution would be measured comprehensively, which will more clearly show the additive effects of environmental hazards on the health of residents.

DEALING WITH DANGERS FROM LEAD

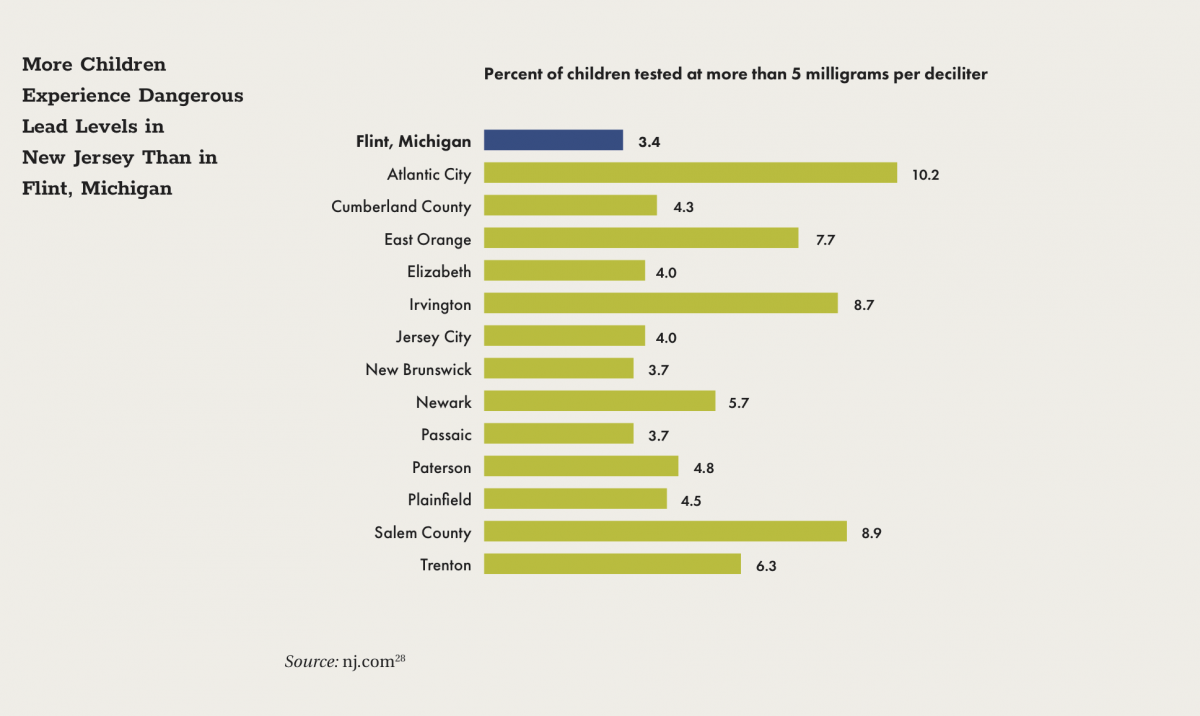

Science shows there is no safe level of exposure to lead, and children are most vulnerable to lead poisoning and the permanent damage it can cause. Eleven New Jersey communities have a higher proportion of young children with dangerous lead levels than does Flint, Mich.

Atlantic City, Irvington, and East Orange had the state’s highest levels. One effort to address the issue of cumulative impacts is under way in Newark, where the city has adopted a municipal ordinance requiring the creation and maintenance of a resource inventory that includes demographic, health, and environmental data.29 The ordinance also mandates that newly proposed commercial and industrial activities reveal the type and amount of pollution they will produce.

A broader state-coordinated approach is needed.

RECOMMENDATION

Significantly step up efforts to test for—and lessen exposure to—lead, and identify new sources of funds to assist with reducing health risks.

Necessary measures include:

- annual testing for lead in drinking water at schools, day-care centers, and pre-schools;

- requiring municipalities to conduct lead paint inspections in one- and two-family rental units;

- mandating soil testing to determine lead content prior to sales of homes that have a higher risk of contamination;

- compiling and granting public access to tests of soil lead levels; and

- adopting a statewide plan to reduce exposure from lead-contaminated buildings, soil, and drinking water.

DIESEL EMISSIONS

Living in urban areas also exposes residents to higher levels of vehicle exhaust than suburban and rural New Jerseyans face. State policy should take this into consideration.

RECOMMENDATION

Mandate significantly reduced diesel particulate-matter emissions, beginning with support for reviving a ban on pre-2007 trucks from ports operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

Improving air quality will have a salutary effect on the health of residents in Newark, Elizabeth, and the surrounding area.

DISASTER READINESS

Though the consequences of climate change are more threatening and immediate in economically distressed neighborhoods and communities of color, many of those communities are unprepared.

RECOMMENDATION

Develop adaptation and emergency plans to address the impacts of climate change, with the involvement of community residents, local community groups, and environmental justice organizations.

Such plans should include steps to be taken for evacuation; police, fire, and public works deployment; and feeding and housing people when a climate-related crisis occurs.