“Buy land,” Will Rogers famously counseled nearly a century ago. “They ain’t making any more of the stuff.” If the vaudevillian-turned-social commentator were alive today, he might advise New Jerseyans: “Preserve land. There ain’t much more of the stuff left.”

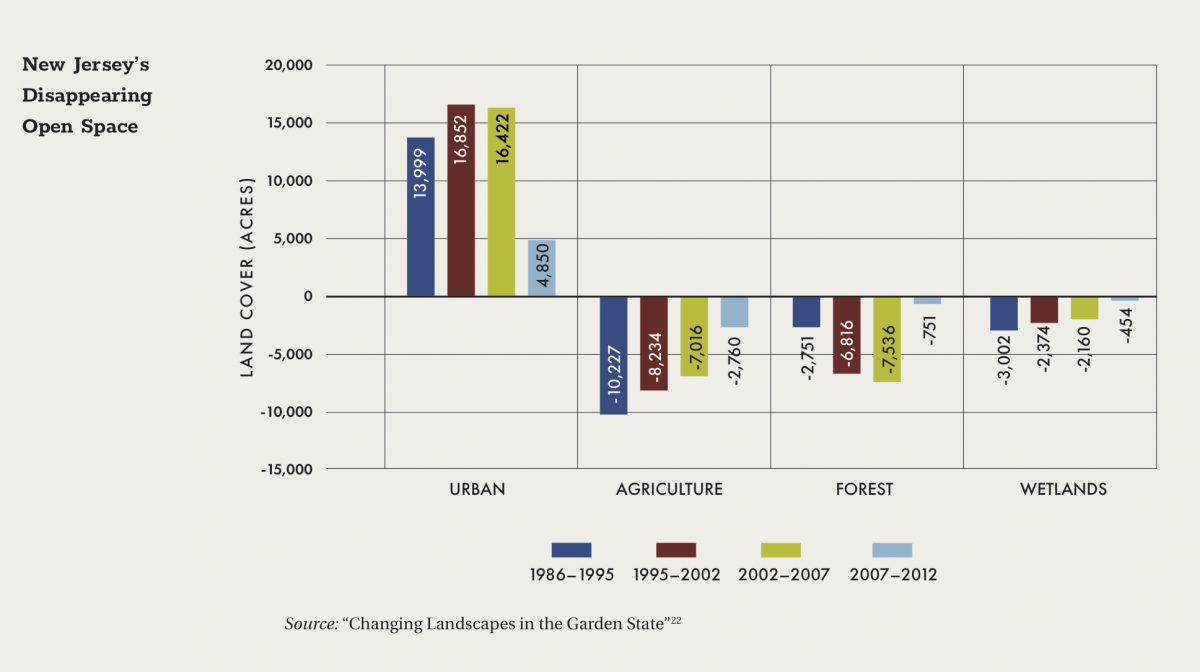

New Jersey is the most densely populated state and the most built-out. More than 2 million of the state’s 5 million acres are fully developed, and an estimated 1.4 million acres are protected by various levels of government. With much of the remaining land unsuitable for development, researchers expect New Jersey to approach near-total build-out by midcentury.21

Preserving and protecting New Jersey’s shoreline, its diminishing open fields, forests, wetlands, highlands, farmland, and parkland are more than a matter of aesthetics. Undeveloped land absorbs rainfall, replenishing aquifers that are major sources of drinking water. The impervious surfaces in fully developed areas prevent rainwater from being absorbed by the ground, causing urban flooding, stormwater runoff, and sewer overflows.

SHORE PLAN LONG OVERDUE

Some municipalities along the Atlantic coast, Delaware Bay, and other low-lying areas are taking steps on their own. These include planning to buy out residents whose homes are severely damaged or destroyed in future storms; amending master plans to return storm-devastated residential areas to open space; requiring foundations of rebuilt homes to be raised several feet above previous levels; and upgrading sewer systems to protect against water contamination from severe flooding. But this is too big a problem to leave to local action.

RECOMMENDATION

Develop a climate-change action plan to address the coastal threats from rising sea levels. The plan should include effective growth-management strategies, sustainable-development practices, and protective shoreline-management plans.

This plan should include an immediate update of the Shore Protection Master Plan. The 35-year-old plan predates decades of development, Superstorm Sandy, the latest revelations about climate change, and the sea-level rise.

STRENGTHENING STATE PLANNING

New Jersey’s development patterns through the last three decades of the 20th century and into the second decade of the 21st have led to suburban sprawl, turning farmland into shopping malls, office parks, and residential developments. This, in turn, has brought more parking lots, streets and sidewalks, and bigger, wider highways that enable commuters to travel greater distances between home and work, increasing motor-vehicle use, gasoline consumption, toxic air pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions.

New Jersey’s first major attempt at curbing sprawl statewide came in 1985, with passage of the State Planning Act. The Act established the State Planning Commission (SPC) and the Office of State Planning (OSP). The SPC was assigned the duty of creating a “coordinated, integrated and comprehensive plan for the growth, development, and conservation of the State and its regions…which…identif[ies] areas for growth, agriculture, open space conservation and other appropriate designations.”23

The commission adopted New Jersey’s first State Development and Redevelopment Plan in 1992, made changes and readopted in 2001, and offered a revision in 2010 that was not adopted. While many municipalities and counties actively participated in a “cross-acceptance” process aimed at linking the goals and objectives of the SDRP with local planning efforts, the effort was doomed by a flaw: the state plan was not binding. It became a haphazardly applied blueprint.

State and regional efforts, critical to climate change adaptation, demand greater urgency.

RECOMMENDATION

Update the State Development and Redevelopment Plan, Pinelands Comprehensive Management Plan, and Highlands Regional Master Plan to address the threats New Jersey faces.

The 2010 version of the SDRP offered a prescient observation (originally attributed to Benjamin Franklin). “Failing to plan,” it declared, “is tantamount to planning to fail.”

Events of recent years bear out this sentiment. The OSP was reconstituted as the Office for Planning Advocacy in the Department of State. The SDRP became the State Strategic Plan, refocused primarily on where state investment should be guided, but was never adopted. The SPC, for all practical purposes, is moribund. According to the last two meetings for which minutes are available, the commission met for three minutes in July 2015 and for seven minutes in January 2016. Seven of its last 11 scheduled meetings have been canceled.

RECOMMENDATION

Remove the Office of State Planning from the Department of State and establish it as an independent agency located in the Department of Treasury .

The State Planning Act provided for the Office of State Planning and the State Planning Commission to be “established in the Department of the Treasury” as an independent body with a director appointed by and serving at the pleasure of the governor. The director was to act as the principal executive officer of the SPC. Over time, the independent authority of the SPC and its staff has been eroded. A return to the organizational infrastructure set forth by the State Planning Act, combined with a commitment to the mission and core principles of the State Planning Act, are necessary to restore the critical role of the SPC and its staff in undertaking sound and integrated statewide planning to protect the environment, revitalize cities and towns, and foster economic growth.24

STRENGTHENING REGIONAL PLANNING BODIES

New Jersey’s efforts at regional planning have been more successful. In 1969, the Legislature established the Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission (“Development” was later dropped from its name). The HMDC statute set up a district comprising 14 municipalities in Bergen and Hudson counties, with the commission largely responsible for converting the Meadowlands from landfill-infested marshland in the basin of the polluted Hackensack River into a transportation and recreation hub boasting 8,400 acres of preserved wetlands and open space.

The commission accomplished this through an innovative tax-sharing plan, under which the municipalities pooled revenue and enjoyed the economic benefits of sharing services and consolidating their planning, zoning, and regulatory functions into a single entity. Despite recent legislation and administrative action that weakened this regional collaboration, the transformation of the Meadowlands has been impressive.

The Pinelands offers another regional planning success. In 1978, Congress created the Pinelands National Reserve, covering 1.1 million acres—or 22% of the state’s total land mass, the largest area of open space between Richmond and Boston. One year later, the New Jersey Legislature passed the Pinelands Protection Act, “to preserve, protect, and enhance the natural and cultural resources of the Pinelands National Reserve, and to encourage compatible economic and other human activities consistent with that purpose.”

The responsibility for carrying out this ambitious goal was placed in a 15-member appointed Pinelands Commission with an unusual level of land-use authority over an area encompassing 53 municipalities in Atlantic, Burlington, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Gloucester, and Ocean counties. Among other powers, the commission can override local land-use and development regulations. Municipalities are required to conform their local master plans and zoning ordinances to the regional plan.

Pursuant to the statute, the commission in 1980 delineated areas where development would be permitted, limited, or prohibited. By law, this Comprehensive Management Plan is updated every five years.

Despite occasional disputes between the Pinelands Commission and its constituent municipalities and counties (as well as the Legislature and the governor), the vision set forward more than three decades ago largely prevails. Nearly half of the Pinelands (460,000 acres) is permanently protected through cooperative state, county, municipal, and private efforts. The New Jersey Pinelands Commission’s annual Long-Term Economic Monitoring Program finds that managed development has overall shown economic benefits for Pinelands municipalities using indicators such as population growth, real estate values, income and employment trends, and municipal finances.25

The New Jersey Highlands Council, established in 2004, lacks the Pinelands Commission’s level of authority. Its jurisdiction covers 859,000 acres spread across 88 municipalities in Bergen, Hunterdon, Morris, Passaic, Somerset, Sussex, and Warren counties.

Like the Pinelands Act, the Highlands Act aims to protect important water supplies—in this case, the sources for 5.4 million New Jersey residents, or 60% of the state’s population. Unlike the Pinelands Comprehensive Management Plan, however, the Highlands Regional Plan is more an advisory document than an enforceable plan of action. It more closely resembles the State Planning Act in this regard, carrying sufficient weight to persuade some municipalities and counties to participate in joint planning efforts but lacking enforcement clout except in a Preservation Area regulated by the DEP. And, like the State Planning Commission, the Highlands Council’s influence depends largely on the attention—or inattention—it receives from the administration in Trenton.

In recent years, some decisions have been made that run counter to the mission of preserving valuable resources and promoting regional solutions. Examples include eliminating regional tax sharing in the Meadowlands and approving a gas pipeline through the Pinelands’ fragile ecosystem. In addition, the DEP has made more land in the Highlands available for development by increasing the number of septic systems allowed there. Corrections are needed to get back on course.

RECOMMENDATION

Appoint members to the State Planning Commission, Pinelands Commission, and Highlands Council who are committed to carrying out these agencies’ missions.

All of these efforts are important to controlling sprawl, reversing unsustainable land-use patterns, slowing the inexorable drive toward build-out, and crafting regional solutions. But more is needed. Along the Atlantic coast and in other tidally influenced areas such as the Delaware Bayshore, Delaware River, and Hudson-Raritan estuary, the threats posed by climate change—beach erosion, tidal flooding and, ultimately, the permanent loss of habitable land to the rising sea—require regional, rather than local, strategies.

BEACH REPLENISHMENT

The Army Corps of Engineers, which has spent an estimated $1.5 billion on New Jersey beach projects over the past 25 years, proposes to spend an additional $1.92 billion for sand dredging and pumping through 2060, to replenish beaches and reconstruct dunes, which will be in ever-greater danger of washing away in extreme weather.26 This is a losing proposition.

Even the best efforts of coastal municipalities to adapt their master plans, zoning ordinances, and building codes to changing climate conditions are no substitute for a larger scope of regional planning and management strategies.

RECOMMENDATION

Conduct a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of all beach replenishment projects involving climate change considerations. The analysis should include alternatives to replenishment as a way to respond appropriately to the risks associated with climate change.